The Sanskrit word vandanam (वन्दनम्) means “offering of prayers. " In bhakti-yoga, vandanam is one of the nine limbs of devotional service (navavidha-bhakti), as described in the Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam.

Those who follow in the footsteps of the great saintly ācāryas are advised to approach the Supreme Lord through prayer. However, it is essential to understand that the efficacy of such prayer lies not merely in its performance but in the mood and manner in which it is offered. One must learn to pray in the mood demonstrated by the ācāryas—a spirit imbued with humility, deep surrender, and a heartfelt longing to serve, rather than to bargain or demand things for ourselves.

Prayer is not offered solely to the Supreme Lord but naturally extends to the guru, the paramparā, and even to the exalted demigods who serve the Lord in various capacities. Yet the mood of such prayers remains consistent—one does not pray for material gain, power, or worldly prosperity, but humbly begs for the shelter of their lotus feet and the mercy to advance in pure devotion. To the guru and paramparā, the disciple prays with a heart full of surrender, longing for the shade of their feet as his only hope for spiritual progress. Even when honoring the demigods, the Gauḍīya devotee approaches them not as independent benefactors but as venerable servants of Kṛṣṇa, praying only for help to serve the Supreme and never for separate, material desires.

Sadly, it has become fashionable within the broader Vaiṣṇava world to pray to Kṛṣṇa in a manner that contradicts the mood and example shown by our Guardians. Increasingly, we see devotees requesting prayers for their loved ones when they are ill or facing adversity. While such sentiments may arise from natural affection and good intentions, this method of praying—where Kṛṣṇa is petitioned to fulfill our material desires or to alleviate our suffering or that of those dear to us—reduces the Supreme Lord to the role of a divine servant. The bhakti-yogī aspires to serve the Lord selflessly, not to diminish Him to the status of a mere order-supplier to fulfill our desires.

In many parts of the modern Vaiṣṇava world—particularly in the West—the influence of Judeo-Christian culture has subtly shaped how devotees approach vandanam. Conditioned by centuries of religious tradition that emphasizes supplication for health, prosperity, and other material benefits, many carry an inherited mindset into their devotional practice. As a result, the Supreme Lord is often approached not as the ultimate object of selfless love and service but as a benevolent provider whose role is to fulfill personal needs. We increasingly see this on social media, where devotees ask other devotees to pray for a friend, family member, and even for those they consider advanced devotees when they fall ill or experience hardship.

But this is not the spirit of bhakti. Bhakti is not about asking God to fulfill our material desires; it is about learning to love and serve Him regardless of our circumstances. When we examine the prayers of the great sādhus and saints of the Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava tradition, we encounter a very different tone. Their vandanam is not centered on personal gain or the alleviation of suffering but is saturated with surrender, longing for service, and a single-hearted desire to please the Lord.

To be fair, the tendency to approach the Divine with a transactional mindset is not exclusive to the Judeo-Christian world. It is also deeply rooted in many streams of Hinduism, where prayers are commonly directed to the demigods—empowered administrative deities of the universe—for blessings of health, wealth, fertility, protection, success, and so on. Even Kṛṣṇa is often approached for such material desires, “Jaya Jagadīśa Hari—give me wealth, health, and a house by the sea!” The mood is familiar: God, or the gods, are seen as providers, and prayer becomes a form of spiritual currency—a bargaining tool: “If You give me this, I will be a good person. I will follow these rules, and in return, I expect material prosperity, good health, a happy life, and heavenly pleasures after death.” Such persons may even envision their God serving them lemonade on a golden platter in heaven.

While such material prayers are not inherently condemned, they reflect a less mature stage of spiritual development. The Vedic tradition does prescribe demigod worship for those still entangled in material desire. However, Śrī Kṛṣṇa, in the Bhagavad-gītā, clarifies the nature of such worship:

kāmais tais tair hṛta-jñānāḥ

prapadyante ’nya-devatāḥ

taṁ taṁ niyamam āsthāya

prakṛtyā niyatāḥ svayā

(Bhagavad-gītā 7.20)

“Those whose intelligence has been stolen by material desires surrender to demigods and follow the particular rules and rituals of worship according to their own natures.”

In other words, when driven by material hankering, the soul naturally gravitates toward lesser deities who can more easily grant specific results. This form of prayer is shaped by one’s nature and developmental stage and is acknowledged as a stepping stone on the broader path—but it remains far from the ideal of śuddha-bhakti, or pure devotional service.

Kṛṣṇa further distinguishes the outcome of such worship:

antavat tu phalaṁ teṣāṁ

tad bhavaty alpa-medhasām

devān deva-yajo yānti

mad-bhaktā yānti mām api

(Bhagavad-gītā 7.23)

“Men of small intelligence worship the demigods, and their fruits are limited and temporary. Those who worship the demigods go to the demigods, but My devotees come to Me.”

The essential difference is this: demigod-oriented prayer seeks to acquire, whereas bhakti-oriented prayer seeks to give. True devotion begins not when we ask God for something, but when we ask to serve.

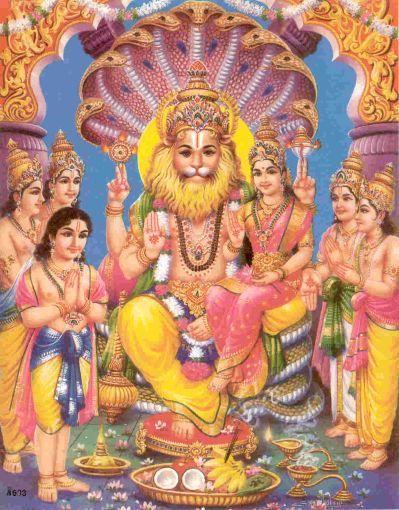

Our Guardians have shown by their example that respectful prayers may be offered to great devotees such as Lord Śiva—revered as the foremost Vaiṣṇava—not for material benefits, but for blessings that aid in the removal of obstacles to devotional service. Similarly, Gauḍīyas commonly pray to Lord Nṛsiṁhadeva, Kṛṣṇa Himself in a fierce protective form, seeking shelter and protection for their bhakti, and the removal of internal anarthas that obstruct their progress. Yet even in these prayers, the mood remains one of pure dependence and longing for service, never petitioning for worldly gain. Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura exemplified this spirit by composing a heartfelt prayer to Lord Nṛsiṁhadeva, beseeching Him not for protection from external dangers, but for the purification of the heart. He writes:

"Within my sinful heart the six enemies headed by lust perpetually reside, as well as duplicity, the desire for fame, plus sheer cunning. At the lotus feet of Lord Nṛsiṁha, I hope that He will mercifully purify my heart and give me the desire to serve Lord Kṛṣṇa."

Thus, even when praying to Lord Nṛsiṁhadeva—an avatāra of Kṛṣṇa—the Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava remains firmly focused on advancing in pure devotion; the consciousness is never diverted. They are seen not as independent powers but as servants and manifestations of the Supreme Lord. Lord Nṛsiṁhadeva, being directly Kṛṣṇa Himself, is never petitioned for material desires. Rather, prayers directed to Him—and to other divine personalities—are understood as assistance in the sādhaka’s journey toward pure, selfless bhakti. Śrīla Bhakti Promode Purī Gosvāmī once emphasized this principle with great clarity. Upon hearing that a devotee had prayed to Lord Nṛsiṁhadeva to punish an external enemy who was troubling the devotees—and that afterward the offender indeed suffered misfortune—he became deeply displeased. He stressed that such a mood is entirely contrary to true Vaiṣṇava prayer. Śrīla Purī Mahārāja instructed that prayers to Lord Nṛsiṁhadeva should not be made for personal protection or retaliation, but solely for the safeguarding of the siddhānta—the pure and living truths of devotion—from distortion and decline.

This contrast is beautifully illustrated by the prayers of the paramahaṁsas—the exalted saints of our Gauḍīya lineage—whose hearts do not burn with worldly desires but with an intense longing for service, remembrance, and the dust of the Lord’s lotus feet.

This mood is perfectly articulated in the fourth verse of the Śikṣāṣṭaka, composed by Śrī Kṛṣṇa Caitanya Mahāprabhu, who revealed the innermost aspirations of the pure devotee:

Śikṣāṣṭakam, Verse 4

na dhanaṁ na janaṁ na sundarīṁ

kavitāṁ vā jagad-īśa kāmaye

mama janmani janmanīśvare

bhavatād bhaktir ahaitukī tvayi

“O Lord, I have no desires to accumulate wealth, followers, beautiful women, or salvation. My only prayer is for Your causeless devotional service, birth after birth.”

Here, Mahāprabhu dismisses the common pursuits of material blessings and expresses a singular, unwavering yearning to eternally serve the Lord with no expectation of reward.

Sri Krsna Caitanya Mahaprabhu in this prayer does not even petition the Lord for residence in Vaikuntha or Goloka where the Supreme Lord engages in personal relationships with His devotees. He asks only for service, birth after birth. The devotee is satisfied with service regardless of the circumstances. Even willing to remain in the material world birth after birth. It is better to be a servant of Krishna residing in hell than a king in heaven with no service.

Of course, it is not wrong to ask something of God. Even materially motivated prayer is considered pious, as it at least acknowledges the Lord’s existence and power. In the Bhagavad-gītā (7.16), Kṛṣṇa affirms:

catur-vidhā bhajante māṁ

janāḥ su-kṛtino ’rjuna

ārto jijñāsur arthārthī

jñānī ca bharatarṣabha

“O best among the Bhāratas, four kinds of pious men begin to render devotional service unto Me—the distressed (ārta), the inquisitive (jijñāsu), the seeker of material gain (arthārthī), and those who seek self-realization (jñānī).”

All four are considered su-kṛtinaḥ—pious souls—but they are not on the same level. The ārta, jijñāsu, and arthārthī still approach the Lord from a position of self-interest. Only the jñānī, who seeks truth and self-realization, and ultimately longs to serve the Lord without any ulterior motive, embodies the consciousness of a bhakti-yogī on the most elevated stage of devotion..

teṣāṁ jñānī nitya-yukta

eka-bhaktir viśiṣyate

priyo hi jñānino ’tyartham

ahaṁ sa ca mama priyaḥ

(Bhagavad-gītā 7.17)

“Of these, the one who desires self-realization is superior. He is always absorbed in thoughts of Me and engaged in Bhakti Yoga. I am very dear to him, and he is very dear to Me.”

Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Ṭhākura directly challenged the Judeo-Christian conception of God as a father whose role is to care for us. He instead taught that true bhakti is not to receive care from God, but to offer care to Him—even to serve Him as His parent. He wrote:

“By attributing Fatherhood to Divinity, we can only demand some service from Him and later express gratitude. But expressing gratitude is not rendering devotional service, nor is it a symptom of love. The concept of service from the father on one hand and of expressing gratitude on the other is founded on partial realization. This is not the same as having the unalloyed desire for the happiness of the Lord; this is not devotional service.

In the concept of demanding service and expressing gratitude, there is an inherent element of calculation, of give and take. The causeless and uninterrupted desire to serve the Lord cannot develop from this. This underdeveloped concept of theism can blossom fully when one attributes son-hood to Divinity. In the concept of (the Lord’s) Fatherhood the son’s true identity (as the eternal servant of the Lord) is not revealed, but in the concept of (the Lord’s) son-hood the father’s identity (as His eternal servant) is fully included.

Ātmā vai jāyate putraḥ—it is the ātmā (the parent) who gives birth to the son. The son cannot serve his father from the beginning, but the father can serve his son from the beginning.”

In this light, prayer is reoriented from seeking something from God to offering something to Him, just as a loving father naturally gives to his child without expectation.

The soul’s eternal function—its sanātana-dharma—is to render loving service to the Supreme Lord. Sanātana-dharma refers to the soul’s inherent and unchanging nature, which is beyond all temporary designations of religion, race, culture, creed, and so on. It is not a man-made belief system but the eternal truth of who and what the ātmā is: not a master or controller, but a servant—meant to love, serve, and find fulfillment in a loving relationship with the Divine.

In contrast, the desire to be a master reflects a soul that has turned away from its natural state. It is a diseased condition—a spiritual illness born from misidentification—that leads only to suffering. Until the soul reawakens its true identity, no amount of external achievement can bring genuine fulfillment. Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu clearly revealed the soul’s original nature:

jīvera 'svarūpa' haya — kṛṣṇera 'nitya-dāsa'

kṛṣṇera 'taṭasthā-śakti' 'bhedābheda-prakāśa'

(Caitanya-caritāmṛta, Madhya 20.108)

"The constitutional nature of the living entity is to be an eternal servant of Kṛṣṇa. He is the marginal energy of Kṛṣṇa and a manifestation simultaneously one with and different from the Lord."

This fundamental truth—that the ātmā is the eternal servant of the Lord—serves as the cornerstone of spiritual life. When this truth is forgotten, it becomes the root cause of bondage. Mistaking itself for the enjoyer of matter rather than the enjoyed—a conscious being meant for Kṛṣṇa’s pleasure—the living entity abandons its natural service position and instead aspires to dominate material energy. In this misguided pursuit of fulfillment as a false master, it turns away from the source of all joy, Kṛṣṇa. Yet, no matter how much it may achieve or accumulate in this world, frustration inevitably follows. Just as a fish cannot survive outside of water, the ātmā, when separated from the ocean of devotional service, flounders and suffers—restless, suffocating, and out of place. Its true nature is that of a servant, and only by returning to the jiva's true nature through the practice of bhakti yoga does it find peace.

Real peace, real joy, real life—ānanda—awaken only when the soul is restored to its natural position in loving service to the Lord.

This transformation from craving mastery to yearning for service is exemplified in the life of Dhruva Mahārāja. As a child, he was deeply wounded by rejection and insult, prompting him to seek a great kingdom. Through intense austerity and determination, he sought the Lord to fulfill his material desires—but when Kṛṣṇa appeared before him, everything changed. His heart melted in the presence of the Lord. The desires that had fueled his efforts now felt hollow and insignificant in the face of the Lord, the embodiment of Love. After his darshan, his desires transformed from material desires to spiritual desires.

In a moment of pure realization, Dhruva reflected:

aho bata mamānātmyaṁ

manda-bhāgyasya paśyata

bhava-cchidaḥ pāda-mūlaṁ

gatvā yāce yad antavat

(Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam 4.9.31)

“Alas, just see my misfortune. I approached the lotus feet of the Supreme Lord, who alone can free me from the bondage of birth and death—yet I foolishly asked for things that will perish.”

This is the hallmark of śuddha-bhakti—pure devotion: not the suppression of desire, but its divine transformation. The soul is never without longing; desire is intrinsic to its very nature. It cannot be eliminated, only redirected. In conditioned life, that longing is misdirected toward fleeting external objects. The soul becomes entangled in the pursuit of material success, power, recognition, and sensory pleasure, believing that these temporary achievements will bring lasting satisfaction. However, when the atma/self is touched by divine grace—whether through the darśana of the Lord or the association of a pure devotee—its inner compass is realigned, and it begins to awaken to its true nature. In truth, every soul is searching for enjoyment and happiness because pleasure is the inherent goal of all living beings. Yet, the soul seeks love in all the wrong places, chasing reflections of bliss in the shadows of the material world. The real fulfillment of all desire rests at the feet of Kṛṣṇa. Only a relationship with Him can satisfy the heart's deepest longing and bring eternal happiness.

Our Guru Mahārāja, Jagad Guru Swāmī B. G. Narasiṅgha Mahārāja, once said:

“Most material prayers don’t even make it to Kṛṣṇa—the demigods intercept them.”

Believing that the Supreme Lord personally manages every request for money, health, or other material needs is a misunderstanding of His nature and interests.

To approach Kṛṣṇa for material benedictions is like approaching a billionaire just to beg for ten cents. When one has the opportunity to petition the all-loving and all-powerful Supreme Person, it is a tragic misuse of that moment to ask for something trivial and temporary. Why not ask for the best thing of all?

Only such prayers, born from seva-bhāva, transcend the realm of transactional religion and are the most pleasing to the Supreme Lord. That alone is truly worthy of the name vandanam.

Consider the prayer of Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura:

“manasa, deha, geha—yo kichu mora / arpiluṅ tuwā pade, nanda-kiśora”

“Mind, body, family, whatever I possess—I offer everything at Your lotus feet, O Nanda-kiśora/Krishna.”

(Śaraṇāgati, “Bhaktivinoda’s Surrender”)

This prayer expresses complete surrender rather than a request for comfort. He does not say, “Please fix my worldly problems,” but rather, “Everything is Yours—do with me what You will.”

In the Śikṣāṣtakam of Sri Krishna Caitanya Mahaprabhu we are given the heart of Vaishnava prayer in verse 8

āśliṣya vā pāda-ratāṁ pinaṣṭu mām

adarśanān marma-hatāṁ karotu vā

yathā tathā vā vidadhātu lampaṭo

mat-prāṇa-nāthas tu sa eva nāparaḥ

“Let Kṛṣṇa tightly embrace me, or trample me under His feet, or break my heart by not being present before me. He is a debauchee after all. Yet He alone is the Lord of my life.”

(Śikṣāṣṭakam 8, by Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu)

This is the essence of pure devotion—śuddha-bhakti. No demands. No bargaining. No expectation of reciprocation. Just surrender.

The story of the great saint Prahlāda Mahārāja perfectly illustrates the uncompromising mood of the pure devotee when it comes to petitioning the Lord for material gain.

Though born as the son of the powerful demon king Hiraṇyakaśipu, Prahlāda was a pure devotee of Vishnu/Kṛṣṇa from early childhood. Raised in an environment steeped in hostility toward the Supreme Lord, he remained fearless and unwavering in his devotion, even when subjected to violent persecution. Thrown into fire, cast from cliffs, and trampled by elephants—no matter the cruelty inflicted upon him, Prahlāda remained unharmed. Yet even in the face of such extreme oppression, he never prayed for protection. Knowing that the Lord naturally guards His surrendered devotee, Prahlāda saw no need to petition for safety. True devotion rests on complete faith: the genuine devotee understands that Kṛṣṇa’s protection is already assured by surrender, not by repeated requests born of fear.

Thus, even under the most harrowing circumstances, Prahlāda exhibited perfect trust in the Lord’s shelter. A true devotee approaches the Supreme not with demands, fears, or bargains, but with a heart yearning only for service.

Eventually, the Lord Himself appeared as Nṛsiṁhadeva—the ferocious half-man, half-lion incarnation of Viṣṇu—to vanquish the demon Hiraṇyakaśipu and protect His devotee. After slaying the tyrant, Nṛsiṁhadeva offered Prahlāda any boon he desired. Yet Prahlāda, untouched by even the slightest desire for material reward or liberation, humbly asked for nothing but the opportunity to remain forever engaged in the Lord’s service:

manny gatiḥ sa tu gatiḥ punar gatiḥ

tvat-pāda-sevābhirataḥ kadā nu

"My Lord, I do not wish for liberation or material gain—my only desire is to be engaged in Your service."

(Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam 7.10.6, paraphrased)

Apart from his own aspiration for eternal service, Prahlāda requested only one other thing: that his father, despite his grievous offenses, be forgiven and purified. In this way, Prahlāda revealed the heart of the pure devotee—one who neither strikes bargains with God nor seeks personal advantage, but who remains the well-wisher of all beings, even of those who have hated and harmed him.

Another striking example of the true spirit of Vaiṣṇava prayer is found in the supplications of Queen Kuntīdevī—a royal mother who endured unimaginable suffering and political intrigue. Kuntī did not ask the Lord for safety, wealth, or ease. Instead, she prayed:

vipadāḥ santu tāḥ śaśvat

tatra tatra jagad-guro

bhavato darśanaṁ yat syād

apunar bhava-darśanam

“I wish that all those calamities would happen again and again, so that we could see You again and again, for seeing You means that we will no longer see repeated birth and death.”

(Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam 1.8.25)

Queen Kuntī viewed her trials and tribulations not as curses but as blessings from the Lord, as they kept her in constant remembrance of Him. In her distress, her mind naturally turned to Kṛṣṇa, and that remembrance was, for her, the greatest reward.

In this same spirit, the Vaiṣṇava does not pray for his own liberation, nor does he seek personal gain. His only prayer is to love and serve the Lord. Viewing all living beings as servants of God, he urges them to awaken to their sanātana-dharma—their eternal nature as devotees. The Vaiṣṇava is kṛpālu—a compassionate well-wisher of all. His very presence becomes a channel for divine grace, naturally drawing the mercy of the Lord and extending it to others.

titikṣavaḥ kāruṇikāḥ

suhṛdaḥ sarva-dehinām

ajāta-śatravaḥ śāntāḥ

sādhavaḥ sādhu-bhūṣaṇāḥ

“The symptoms of a sādhu are that he is tolerant, merciful and friendly to all living entities. He has no enemies, he is peaceful, he abides by the scriptures, and all his characteristics are sublime.”

(Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam 3.25.21)

Such a saint does not ask the Lord to change the world to suit him. Instead, he adapts himself for the service of the Lord, even in the most difficult circumstances.

As Śrīla Bhakti Rakṣaka Śrīdhara Deva Goswāmī Mahārāja taught, ‘The environment is friendly. ' Such a devotee sees no fault in the environment. Rather, he understands that everything we encounter is arranged by the Supreme Lord for our upliftment.

If we are sincere, we must adjust ourselves to the environment. Instead of blaming others or circumstances, the Vaiṣṇava seeks inner transformation, understanding that the path to peace lies not in controlling the world but in aligning the heart with the will of the Lord.

Similarly, the Stoic philosophers of ancient Greece and Rome—such as Zeno, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius—taught that peace is found not by controlling external events but by mastering one’s inner life. They emphasized accepting all circumstances with equanimity and viewing every difficulty as a means for self-purification and growth. In this, their wisdom echoes the Vaiṣṇava vision: true peace comes not from reshaping the environment but from reshaping the heart in alignment with the Divine will.

However, this attitude of acceptance does not imply that a devotee becomes a masochist, passively enduring harmful or unfavorable situations without discernment. Acceptance of the environment involves recognizing the Lord’s arrangement while also making sincere efforts to create a setting conducive to bhakti. The Six Gosvāmīs of Vṛndāvana exemplified this spirit by clearing forests, uncovering sacred places, establishing temples, and creating an atmosphere that nurtured remembrance of Kṛṣṇa. Even earlier, while still employed under Muslim rulers, Rūpa and Sanātana Gosvāmīs cultivated a devotional environment within their own residences, transforming their homes into sanctuaries centered on service to Kṛṣṇa. Even in household life, this principle is upheld when an altar is established, daily worship is performed, and the entire home becomes a sacred place dedicated to serving the Lord. Thus, the sincere devotee adjusts both heart and surroundings, not for selfish comfort but to better foster remembrance and service to Krishna.

The gopīs of Vṛndāvana embody the highest ideal of prayer—pure, selfless longing for Kṛṣṇa’s pleasure, utterly untouched by personal desire. Their prayers are not cries for protection, liberation, or reward, but the desperate yearning of the soul to serve the Beloved at any cost. This supreme mood was vividly revealed in one of Kṛṣṇa’s playful yet profound līlās. Pretending to suffer from an unbearable headache, Kṛṣṇa asked Nārada Muni to find a cure: He said only the dust of His devotees’ feet could relieve His pain.

Nārada immediately set out, approaching great sages, kings, and even the queens of Dvārakā. Yet all hesitated, fearful of committing an offense by placing their foot dust upon the Lord’s sacred head. But when Nārada reached Vṛndāvana and explained the situation, the gopīs responded without a moment’s hesitation. Eagerly, they offered the dust from their feet, willing to embrace any consequence—even eternal damnation—if it would bring even the slightest relief to Kṛṣṇa’s suffering. They cared nothing for their own welfare; their hearts were consumed only with the desire to see Him happy. Even in the agony of separation, their prayers were for Kṛṣṇa’s joy alone. In this way, the gopīs revealed the highest pinnacle of devotion—the complete sacrifice of self for the happiness of the Beloved.

The Vaiṣṇava realizes that everything in the environment reflects the soul’s inner condition, and nothing occurs by chance. There is perfect order in the universe, and whatever comes to us is arranged by the Supreme Lord for our purification and upliftment. Rather than blaming others or circumstances or viewing oneself as a victim, the devotee sees the environment as faultless—an instrument designed to reveal his own shortcomings and guide him toward surrender. He understands that all difficulties arise from within as the result of his own past karma and therefore accepts every situation without resentment. Even when the environment seems harsh, he bows his head in humility, acknowledging that no one else is to blame but himself.

In this spirit of deep introspection and surrender, the purified devotee does not pray for relief from suffering, knowing well that all such conditions are temporary and insignificant in the larger journey of the soul. However, the paramahamsa is very disturbed by the suffering of others. Knowing the solution to the problem of suffering, he goes out of his way to help the suffering jivas.

The Vaiṣṇava is naturally the well-wisher of all living beings. Without needing to petition the Lord directly, the mercy of Kṛṣṇa flows wherever His devotee’s compassion is directed. Just as the sun nourishes all without distinction, the heart of a pure devotee radiates goodwill, and that alone can draw divine grace upon others. The Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam 11.2.52 declares:

na yasya svaḥ para iti

vitteṣv ātmani vā bhidā

sarva-bhūta-samaḥ śāntaḥ

sa vai bhāgavatottamaḥ

“When a devotee gives up the selfish conception by which one thinks “This is my property, and that is his,” and when he is no longer concerned with the pleasures of his own material body or indifferent to the discomforts of others, he becomes fully peaceful and satisfied. He considers himself simply one among all the living beings who are equally part and parcel of the Supreme Personality of Godhead. Such a satisfied Vaiṣṇava is considered to be at the highest standard of devotional service.”

sādhavo hṛdayaṁ mahyaṁ

sādhūnāṁ hṛdayaṁ tv aham

mad-anyat te na jānanti

nāhaṁ tebhyo manāg api

“The pure devotee is always within the core of My heart, and I am always in the heart of the pure devotee. My devotees do not know anything else but Me, and I do not know anyone else but them.”

(Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam 9.4.68)

It is not possible for Kṛṣṇa to ignore His devotee. Though He is fully independent and the Supreme Controller of all worlds, Kṛṣṇa willingly becomes subordinate to the love of His bhakta. So deep is His affection for the devotee that He not only protects and uplifts the devotee himself but also extends His mercy to those connected to that devotee.

Our ācāryas have explained that a sincere Vaiṣṇava, by his devotion alone, can deliver many generations of his family. The Skanda Purāṇa and other scriptures affirm that both paternal and maternal ancestors of a pure devotee are uplifted, even if they themselves did not perform any devotional service. Simply by being related to the devotee, they become recipients of the Lord’s special grace.

This mercy is not due to their own merit, but because they are dear to someone who is dear to Him. In this way, Kṛṣṇa’s love for His devotee transcends the normal laws of karma. Even if the family members are unaware of the Lord or have no devotion themselves, they are touched by His kindness because of their relation to the bhakta.

This divine principle is seen in the life of Prahlāda Mahārāja, whose demoniac father Hiraṇyakaśipu was nonetheless granted liberation due to Prahlāda’s purity. Similarly, in the case of Dhruva Mahārāja, his exalted mother Sunīti—herself a virtuous and devoted soul—was further honored and elevated because of her intimate connection to her son's unwavering devotion.

Such is the unparalleled power of bhakti. The devotee becomes not only the beloved of the Lord, but also a channel of liberation for others.

The true art of prayer is realized—not by asking the Lord to serve us, but by offering ourselves fully in His service, just as our exalted predecessors have done. Our prayers should not echo the voice of worldly need, but rather the pure cry of a surrendered soul who seeks nothing but the shelter of Kṛṣṇa’s lotus feet—regardless of circumstances.

Prayer is meant to be the soul’s heartfelt outpouring—but when it becomes formalized and routine, it loses its life. Even in bhakti circles, there is a risk of reducing vandanam to memorized recitations devoid of feeling. Bhakti must be living, not mechanical. When prayer is offered out of habit or social expectation, it becomes a performance rather than an offering of the heart.

True prayer is not measured by eloquence or quantity, but by sincerity. One honest cry from the heart reaches further than a thousand lifeless mantras. Prayer must be alive—born not from pressure, but from longing. It must be lived, not just spoken.

The Supreme Prayer of the Age

Throughout Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava scripture, prayer is revealed as far more than mere petition or repitition—it is the soul’s sincere outpouring of surrender, glorification, and longing for loving service to the Lord.

We do not need to look to the methods or moods of prayer found in other traditions. For those in the line of Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu, the purest and most effective form of prayer has already been revealed. Our path is illuminated by the prayers of Mahāprabhu and our ācāryas—those who have realized the highest truths and demonstrated the deepest expressions of devotion. In following them, we follow the most direct and powerful current to the lotus feet of the Lord.

From this ocean of transcendental prayer, a single prayer has been revealed as the most potent, most accessible, and most essential for the age of Kali—the Mahāmantra:

Hare Kṛṣṇa Hare Kṛṣṇa

Kṛṣṇa Kṛṣṇa Hare Hare

Hare Rāma Hare Rāma

Rāma Rāma Hare Hare

This divine mantra is not merely a sound formula but the most complete expression of prayer in this fallen age. It contains no request for anything material, no petition for safety, wealth, liberation or any material boon. It is simply a cry for divine service—for engagement in the eternal sevā of Rādhā and Kṛṣṇa.

It is for this reason that Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu, the Golden Avatāra, taught nāma-saṅkīrtana—the chanting of this Mahāmantra—the very heart of His movement, declaring it to be the yuga-dharma, the divinely ordained process for self-realization in Kali-yuga. The Holy Name is nāma cintāmaṇiḥ—a wish-fulfilling gem. It fulfills the deepest need of the soul: reconnection with the Supreme.

Chanted with humility, sincerity, and yearning, with the proper conception under the guidance of a pure Vaishnava the Mahāmantra becomes the soul’s most intimate and elevated prayer—calling not for anything from Kṛṣṇa, other than His loving service.

This is the art of prayer as revealed by our ācāryas—not a negotiation with the Divine, but a sacred offering of the heart. Why imitate the habits of transactional religions seeing Krishna as our order supplier? It is better we take shelter in the footsteps of those exalted saints who have shown us how to pray by their example.

Chant the Holy Name—not as a formula, not as a performance, but as our most honest cry for connection, in love with Krishna. That is transcendenal vandanam. That is bhakti. That is the most powerful method of prayer and will automatically fulfill the needs of every living.