It was in the year 1868 that Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura, then known as Śrī Kedarnath Dutta, found the welcome opportunity to carefully study the teachings of Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu while posted at Dinajpur (now in Bangladesh). On the worldly side, Śrī Kedarnath Dutta was a responsible householder, exceptionally honest and capable high ranking government official, a prolific writer, well known and well liked by one and all. However, the real existence of Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura was in his inner pursuit of the essence of religion which eventually led him to the lotus feet of Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu.

Emerging philosophies based on liberal and rationalistic ideas in the West were shaping the modern world. Whereas, spurred by the infusion of western ideologies brought by the civilising missions of the British, colonial Bengal had become an epicentre of religious, philosophical, and intellectual discourse within India. Brahmo religion and Christianity had particularly become popular among the educated and influential circles in Bengal. His interactions with prominent Hindu social reformers such as Dvijendranath Tagore, Satyendranath Tagore, Ishvar Chandra Vidyasagar, Keshub Chandra Sen, and Nabagopal Mitra, as well as numerous British officials and Christian missionaries, provided Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura with the opportunity to study and discuss diverse contemporary philosophies.

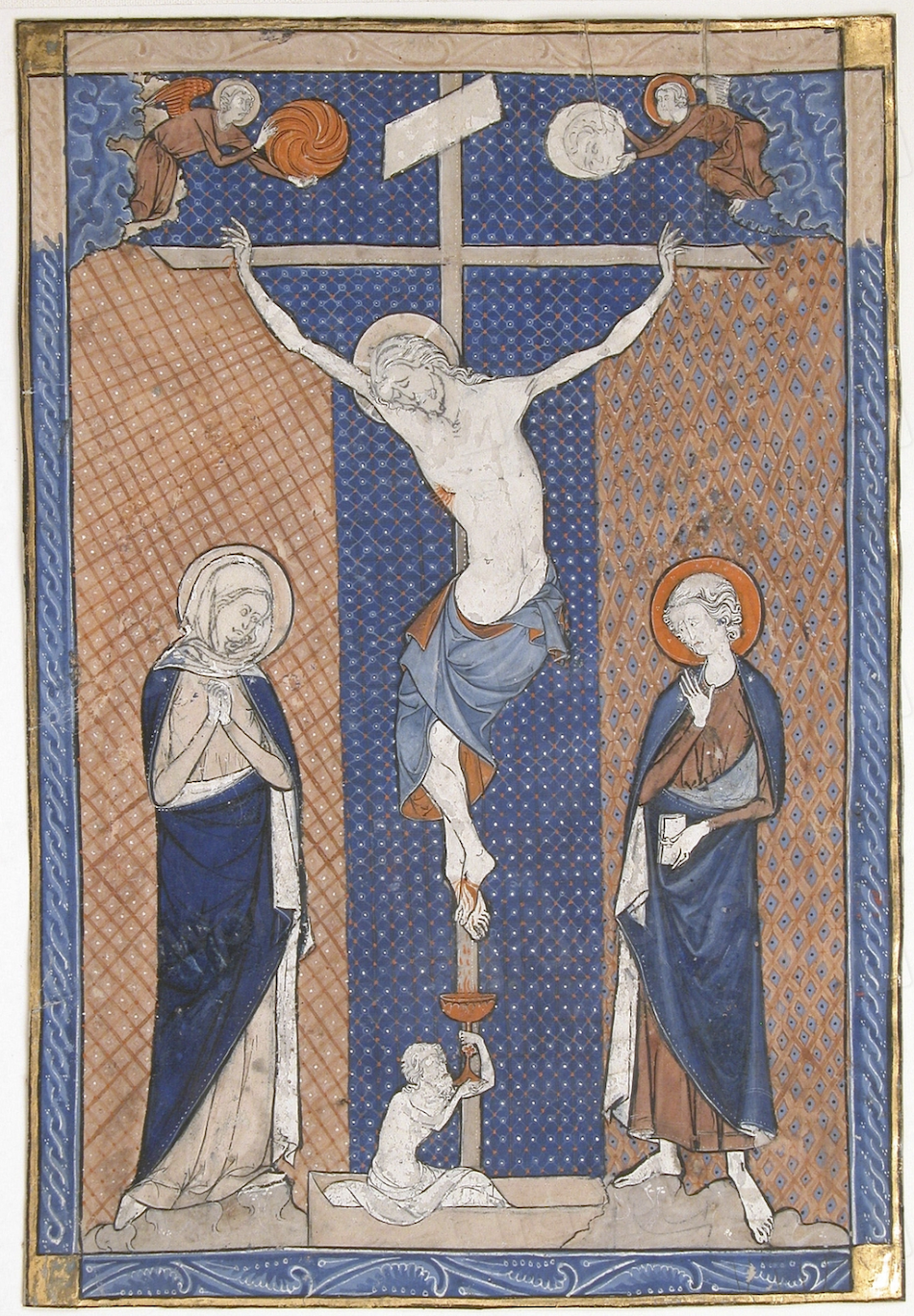

From a young age, Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura was deeply convinced of the existence of a personal God and showed a natural inclination towards devotion. Consequently, he regarded Christianity and the worship of Jesus Christ as superior to Brahmoism, which he considered “bereft of religion and rasa.” At the same time, he could not completely reject the idea of formlessness, which he thought had a place in absolute reality. He writes in his Svalikhita Jīvanī, “Formlessness and essential form, how these two might both be true, that I did not understand.” An intuition that he later found convincingly validated in the philosophy of Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu.

The study of Śrī Caitanya Caritamṛta produced a profound conviction within Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura in the divinity of Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu and His teachings. In Mahāprabhu’s conception there is full fledged development of theistic thought based on the principles of Śrīmad Bhāgavatam, culminating in prema-bhakti towards the supreme person Śrī Kṛṣṇa. In comparison, he could notice the degree of theistic thought or the lack of it, in theories he had come across before.

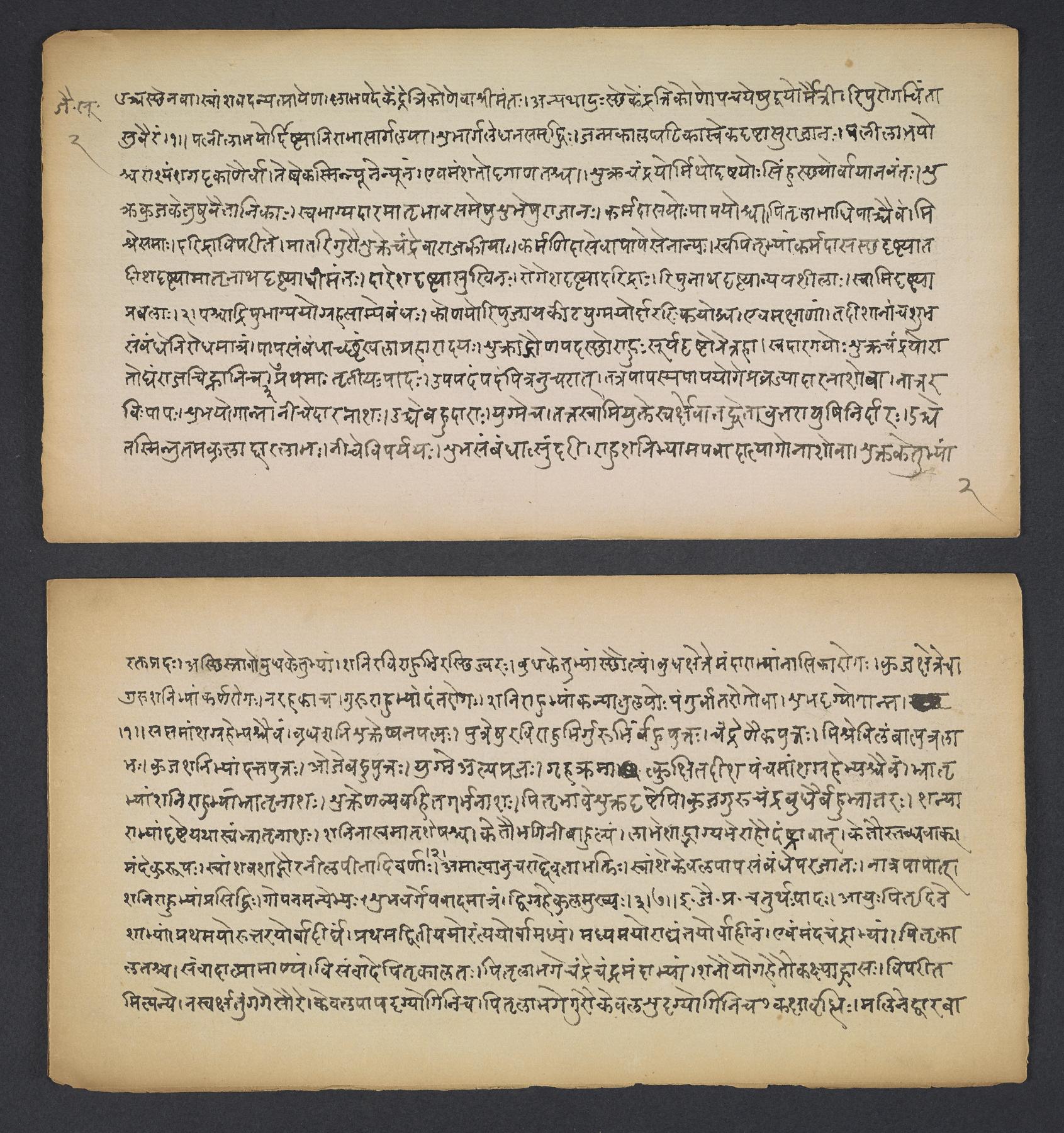

Published in 1893, Tattva Viveka is among Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura's many exceptional works, offering insightful critiques of various philosophies. Written in Sanskrit verse form with accompanying Bengali commentaries, the text delves into the fundamental nature of these philosophies, the historical contexts of their origins, and the reasoning methods they employ. The following sections explore this significant work, focusing on specific key topics.

On Christianity and Western Philosophies

Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura had some appreciation for Chrisitianity owing to the presence of a personal God and a practice of worship. Nonetheless, he was aware of several fallacies in the religion. In Tattva Viveka, going through the many dogmas in Christianity, he notes—

Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura had some appreciation for Chrisitianity owing to the presence of a personal God and a practice of worship. Nonetheless, he was aware of several fallacies in the religion. In Tattva Viveka, going through the many dogmas in Christianity, he notes—

“‘The salvation of jīvas by penalising the God born among the human beings’ — this doctrine is not intelligible to normal reason.”

He also questions the concept of single life, the lack of information on the nature of the soul, the denial of soul in non-human species, among many other absurdities in the religion.

Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura historically traces the Christian Trinity, comprising the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, to Zarathustra's philosophy. Zarathustra, who had Indian roots, relocated to Persia after his non-Vedic concepts failed to gain acceptance in India. He introduced dualistic concepts of good and evil represented by two opposing deities, which inspired the concept of Satan in Christianity and Islam. This dualism evolved into the idea of three separate gods, which later converged into a tripartite understanding of one God, and eventually was unified into a single divine essence. However, Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura states, "Particularly in places which are extremely uncivilised, monotheism of a transcendental (viśuddha) type cannot be found."

Among the western philosophers, materialists like Democritus and Baron d'Holbach are highlighted for emphasising the primacy of matter and dismissing metaphysical explanations. Their Indian counterparts include Cārvāka, who advocated for sensory pleasures and rejected spiritual concepts, and Jaimini, whose interpretation of Mīmāṃsā philosophy is often viewed as materialistic due to its focus on rituals. In the realm of positivists and secularists, Comte and Mill are noted for advocating that all knowledge should be derived from scientific inquiry, with morals and selflessness leading the society instead of spiritual considerations. Sceptics such as Hume challenged the certainty of knowledge, a perspective that resonates with the critical inquiry found in Indian Buddhist traditions. Regarding the sceptics process of doubting whatever exists, Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura makes the following observation —

Among the western philosophers, materialists like Democritus and Baron d'Holbach are highlighted for emphasising the primacy of matter and dismissing metaphysical explanations. Their Indian counterparts include Cārvāka, who advocated for sensory pleasures and rejected spiritual concepts, and Jaimini, whose interpretation of Mīmāṃsā philosophy is often viewed as materialistic due to its focus on rituals. In the realm of positivists and secularists, Comte and Mill are noted for advocating that all knowledge should be derived from scientific inquiry, with morals and selflessness leading the society instead of spiritual considerations. Sceptics such as Hume challenged the certainty of knowledge, a perspective that resonates with the critical inquiry found in Indian Buddhist traditions. Regarding the sceptics process of doubting whatever exists, Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura makes the following observation —

"If properly reviewed it will be revealed that scepticism is only useless raving. “Whether I exist or not?” Who is the person maintaining this doubt? Since I am maintaining this doubt, I definitely exist."

In conclusion, Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura particularly notes that the western intellect is quite materialistic. He says,

“Being incapable of realising the subtle distinction between spirit and matter, they ascertain the material mind or the subtle body (liṅga śarīra) itself as the ātma.”

He feels that no essence can be found in their philosophies and compares the endeavour to the useless act of pounding empty chaff to extract rice.

On Pure Reasoning & Natural Religion of Ātma

For pure reasoning, he says, spiritual knowledge intrinsic to the ātma (jñānaṁ sāhajikam), which is naturally untouched by matter, is the only reliable basis. Whereas, mixed reasoning results from distortion of this characteristic knowledge due to material covering of the ātma. It can only give rise to crooked logic (tarka) mixed with karma or jñāna. Mixed reasoning is condemnable because of the four types of defects inherent in it, viz., bhrama (tendency to commit mistakes), pramāda (tendency to be in illusion), vipralipsā (tendency to cheat) and karaṇāpātava (dependence on imperfect senses). Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura goes on to enumerate the following knowledge innate to the ātma —

- I exist

- I will continue to exist

- There is bliss (ānanda) innate within me

- There is a certain great principle which is the shelter (āśraya) of my bliss

- It is my nature to depend upon that great shelter

- I am eternally devoted (anugata) to that shelter

- The shelter is exceedingly beautiful

- I am incapable of renouncing that shelter

- My present condition is lamentable (śocanīya)

- Rejecting this lamentable position, I should again cultivate a relationship with that shelter.

- This material world is not my eternal home

- My eternal well being is not in material progress

He states that ātma is a spiritual entity (cit), and the nature (svarūpa paricaya) of cit is free-will, whereas bliss (ānanda) is it's function (vṛtti paricaya) — ānandaścidguṇaḥ proktaḥ (Tattva Viveka 2.10). Hence the function of the ātma is the cultivation of bliss. There is a basis to this bliss (āśraya), and the tendency to worship that āśraya (shelter) is natural to the ātma irrespective of the logical direction of the intelligence (buddhi). In the state of material bondage, due to the cover of ignorance, the ātma takes shelter of matter for pleasure, whereas by the culture of transcendental bliss of service towards the Supreme Person who is the embodiment of all bliss (akhila-rasāmṛta-mūrtiḥ), the ātma is reinstated to its natural position (svarūpeṇa vyavasthitiḥ).

To illustrate the point that worship of a shelter (āśraya) is natural to the ātma, Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura relates the following incident while reviewing Godless conceptions—

"The other day I met a Buddhist from Burma and asked him some questions. He replied, “God is without beginning. He has created the universe. He Himself appeared as Buddha and now he is in heaven. By performing pious activities and by following the rules we will reach His abode.” The words of that Buddhist clearly shows that he has not studied the doctrine of Buddhism. He has only explained Buddhism, according to his human nature.

"All such crooked logic (of godless philosophies) cannot be accepted as beneficial to human society. They will only be locked in the books and the hearts of their teachers. Whereas, the followers of these philosophies will accept natural ideas arising from human nature as religion. Comte’s altruism (viśvaprīti), Jaimini’s God in the form of apūrva present in his atheistic karmavāda and Śākyasiṁha’s (Buddha’s) annihilation of self by negation of matter (jaḍa-nirvāṇa-vāda) will only be transformed by their followers into a natural form of religion. This is exactly what has happened."

Tattva Viveka thereby observes that in spiritual matters if a religion is established over the foundation of natural knowledge, then it can be accepted as authentic.

On Various Darśanas (Indian Philosophical Systems)

In Tattva Viveka, Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura criticises Sānkhya, Nyāya, Vaiṣeśika, and Karma-mimāmsa for their lack of recognition of a personal, supreme deity and for their incomplete or materialistic approaches. Sānkhya’s dualism and denial of God, Nyāya’s focus on logic without defining ultimate benefit, Vaiṣeśika’s atomic theory excluding a supreme Lord, and Jaimini’s emphasis on rituals (karmavāda) without devotion are seen as flawed. Tattva-viveka argues that these philosophies lead to secularism or atheism and are insufficient for true spiritual knowledge and liberation. Whereas, reviewing Pātañjali’s yoga śastra, he notes,

In Tattva Viveka, Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura criticises Sānkhya, Nyāya, Vaiṣeśika, and Karma-mimāmsa for their lack of recognition of a personal, supreme deity and for their incomplete or materialistic approaches. Sānkhya’s dualism and denial of God, Nyāya’s focus on logic without defining ultimate benefit, Vaiṣeśika’s atomic theory excluding a supreme Lord, and Jaimini’s emphasis on rituals (karmavāda) without devotion are seen as flawed. Tattva-viveka argues that these philosophies lead to secularism or atheism and are insufficient for true spiritual knowledge and liberation. Whereas, reviewing Pātañjali’s yoga śastra, he notes,

"The god accepted in the sādhana stage is not seen after the attainment of kaivalya, and nothing has been mentioned about the relation of that God with the jīva who has attained kaivalya. If the jīvas on the attainment of kaivalya get merged with that God, then this doctrine is not different to advaitavāda."

In one of his Śaraṇāgati songs, keśava tuwa jagata vicitra, Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura categorically rejects all these philosophies as meant only to ‘cheat the materially inclined’ (vaimukha vañcane). He writes,

tuwā pada-vismṛti, ā-mara jantranā, kleśa-dahane dohi’ jāi

kapila, patañjali, gautama, kanabhojī, jaimini, bauddha āowe dhāi’

tab koi nija-mate, bhukti, mukti yācato, pāta-i nānā-vidha phāńd

so-sabu—vañcaka, tuwā bhakti bahir-mukha, ghaṭāowe viṣama paramād

vaimukha-vañcane, bhaṭa so-sabu, niramilo vividha pasār

danḍavat dūrato, bhakativinoda bhelo, bhakata-caraṇa kori’ sār

“O Keśava, forgetfulness of Your lotus feet has brought on anguish and grief. As I burn in this fire of misery, my would-be saviours — Kapila, Gautama, Kanada, Jaimini, and Buddha — come running to my aid. Each expounds his particular view, dangling various pleasures and liberation as bait in their philosophical traps. They are all cheaters, averse to Your devotional service and thus fatally dangerous. They are magnates of karma, jñāna, and yoga who specialise in opinions and proofs for cheating the materially inclined. Bhaktivinoda, considering refuge at the feet of the Vaiṣnavas as essential, pays his respects to these cheating philosophers from afar.”

On Vedanta-darśana & Advaitavāda

Out of the ṣaḍ-darśanas (six philosophical systems of India) the view of Vedānta-darśana is the only one which fully adheres to the meaning of the Vedas. Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura says,

The vedānta-śāstra by all means expounds devotion to the supreme person. In their commentaries to vedānta-śastra, the erring thinkers have introduced Buddhism disguised as advaitavāda. However, the saintly have presented with great care, the proper commentaries on the Vedānta and thus shown the proper path to the people of the world.

He explores the doctrine of advaitavāda, which claims that the unchanging, formless, and featureless brahman is the only reality. He points out how this doctrine struggles to explain the distinct existence of the material world perceived by countless jīvas, by offering self-defeating arguments. One might question whether simply introducing a theory of illusion (vivartavāda) can make reality disappear. Instead, he says,

"If the inconceivable potency (acintyaśakti) of brahman is accepted, then brahman really remains absolute and there arises no necessity of inventing separate principles. The potency is never different from the potent. The mutually opposite qualities of mutation and immutation, form and formlessness, distinction and non-distinction etc., simultaneously remain in the Supreme without any contradiction due to the power of His inconceivable potency. Since human reasoning is quite limited, it cannot properly realise the inconceivable potency of the Supreme. By the dint of defective human reasoning is it proper to discard the inconceivable potency of the Supreme?"

It is quite reasonable to say that to understand the supreme absolute truth, first and foremost, His acintyatva (inconceivability) must be accepted, honoured, and celebrated. Without this crucial aspect, a philosophy will err by imposing limitations on the unlimited Supreme, and reduce itself to dogmatism.

On acintya-bhedābheda tattva

The acintya-bhedābheda philosophy of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu asserts that the Supreme Being is both inconceivably different and non-different from the individual ātma and the material world. This doctrine harmonises the concepts of duality and non-duality, explaining that the divine and creation are simultaneously one and distinct, beyond human comprehension (acintya).

This approach not only aligns with the deepest insights of the Vedas but also provides a practical path for spiritual advancement, emphasising bhakti as the only means to connect with the supreme. The Supreme Person is unknown and unknowable unless He makes Himself known to us by His grace. He is the sole owner and has sovereignty over everything that exists. However, He is also a true friend to all living entities (suhṛdaḥ sarva bhuteṣu) and can be easily approached through devotion (bhaktyā mām abhijānāti).

According to Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura, only by cultivating a deep relish in serving the lotus feet of Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu (caitanya-caraṇāsvāda) can one internalise the principle of acintya-bhedābheda tattva. This profound realisation is otherwise unattainable through mere intellectual effort.

cintātītam idaṁ tattvaṁ dvaitādvaita-svarūpakam

caitanya-caraṇāsvādāc chuddha-jīve pratīyate

This tattva which is simultaneously different and non-different in svarūpa is beyond contemplation. It is realised in the pure jīva cultivating relish in the service of the lotus feet of Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu. Uncountable contrary qualities in the Lord are adjusted nicely by His acintya-śakti. (Tattva Viveka, 2.8)

The acintya-bhedābheda philosophy of Śrī Caitanya Mahaprabhu completely satisfies the unalloyed reasoning of a sincere seeker, reconciles various thoughts of the Vedas, and bestows the ultimate well-being of the jīvas.

Mahāprabhu’s Mercy

Śrīla Kṛṣṇadāsa Kavirāja Gosvāmi suggests a better use of our tendency for logical reasoning. He says,

Śrīla Kṛṣṇadāsa Kavirāja Gosvāmi suggests a better use of our tendency for logical reasoning. He says,

yadi vā tārkika kahe,--tarka se pramāṇa

tarka-śāstre siddha yei, sei sevyamāna

śrī-kṛṣṇa-caitanya-dayā karaha vicāra

vicāra karite citte pābe camatkāra

Logicians say, "Unless one gains understanding through logic and argument, how can one decide upon a worshipable Deity?" If you are indeed interested in logic and argument, kindly apply it to the mercy of Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu. If you do so, you will find it to be strikingly wonderful.

By applying logical reasoning impartially to understand the various levels of spiritual attainment, one transcends the stages of brahmānanda and vaikuṇṭha-bhakti, ultimately reaching the pinnacle of divine love for Śrī Kṛṣṇa. This highest achievement is expressed through five primary mellows (rasa) as described in the Śrīmad Bhāgavatam: śānta (passive participation), dāsya (servitude), sākhya (friendship), vātsalya (parental affection), and mādhurya (conjugal love). Through the supreme magnanimity of Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu, one can attain prema-bhakti for Kṛṣṇa, a state that remains beyond the reach of even the greatest jñānīs and yogīs. In glorification of Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura, Śrīla Śrīdhar Mahāraja has presented this most precious achievement in a wonderful way in his Bhaktivinoda Viraha Daśakam, where he writes —

yad dhāmnaḥ khalu dhāma chaiva nigame braḥmeti samjñāyate

yasyāmśasya kalaiva duḥkha-nikarair yogeśvarair mṛgyate

vaikuṇṭhe para-mukta-bhṛṅga-charaṇo nārāyaṇo yaḥ svayam

tasyāmśī bhagavan svayam rasa-vapuḥ kṛṣṇo bhavān tat pradaḥ

Merely the effulgence of His divine abode has been designated by the title 'Brahman' in the Vedas, and only the expansion of an expansion of His expansion is sought after with great tribulation by the foremost yogīs. The most exalted of the liberated souls shine resplendent as the bumblebees at His lotus feet. The Primeval Origin of even the Original Śrī Nārāyaṇa who is the Lord of the spiritual sky above Brahman: He is the Original Supreme Lord, the personification of all nectarine mellows - Śrī Kṛṣṇa -- and He is the one that you give.

Although this verse is addressed to Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura, it is understood that he serves as the medium through which Mahāprabhu’s mercy has been extended to the modern world. Aptly called the father of the modern Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava movement, his dedicated and extraordinary efforts revived Mahāprabhu’s teachings, restoring them to the mainstream with full dignity. Writing extensively with an effortless style, he produced a wealth of literature in Bengali, Sanskrit, and English. His essays, original works, commentaries, and devotional songs laid a strong foundation for the propagation of Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu’s Saṅkīrtana movement in the 20th century and beyond. Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura’s visionary work continues to inspire generations of devotees, ensuring the timeless relevance of Mahāprabhu’s teachings, and leaving an indelible mark on the spiritual landscape.