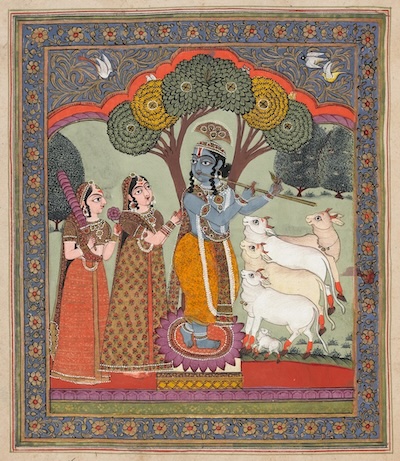

cintāmaṇi-prakara-sadmasu kalpa-vṛkṣa-

lakṣāvṛteṣu surabhīr abhipālayantam

lakṣmī-sahasra-śata-sambhrama-sevyamānaṁ

govindam ādi-puruṣaṁ tam ahaṁ bhajāmi

I worship Govinda, the primeval Lord, the first progenitor who is tending the cows, yielding all desire, in abodes built with spiritual gems, surrounded by millions of purpose trees, always served with great reverence and affection by hundreds of thousands of lakṣmīs or gopīs. (Brahma Saṁhita 5.29)

These descriptions from the Brahma Saṁhita offer us a glimpse into Kṛṣṇa’s abode of boundless wealth and beauty. Unable to comprehend anything of infinite nature, our finite intelligence can only wonder in astonishment if such a place is even possible. Indeed, limitation is the reality of our world that imposes upon us a sense of scarcity and greed which is so unnatural to our real identity as the atma, which is spiritual by nature.

Knowledge sets us free, provided we are looking to be free from material limitations. Ordinarily, by instinct, we are accustomed to compete for material resources, trying to secure what we consider valuable. Although the world hasn’t reached a point where everyone is struggling for basic necessities like food and water, artificial scarcity driven by greed remains a genuine concern. In a broader sense, the question of what constitutes real value, and what is truly valuable, is one that warrants deeper reflection.

It is often said that money makes the world go around. With the kind of technology in place today, where transactions occur in fractions of a millisecond, one could say the world is spinning faster than ever before. The material world is fraught with risks, but today it feels even more so where it is much easier to lose than to gain. Building wealth while minimizing risk is the real challenge. While most people do just enough to hedge against inflationary losses, the more financially astute manage to build substantial wealth. And yet, as the saying goes, "The best laid plans of mice and men often go awry."

When we pause to consider monetary forms and their value, a meaningful historical progression comes into view that may help us better understand our current situation.

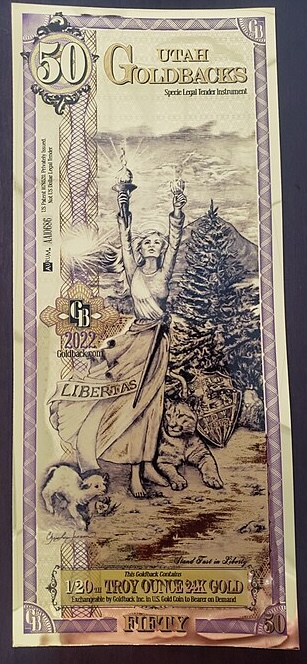

The historically established perspective holds precious metals such as gold and silver as real stores of value. These commodities have retained their position for ages as the most universally acknowledged forms of money. Over time, a dramatic shift in people’s way of thinking along with a general ignorance about the purpose of life has transformed many things, including our understanding of value.

When we started discovering how things work in nature, not only did we find solutions to our problems, but we also started subverting nature on the pretext of better living standards. Religion was replaced with science, and the industrial revolution that began in the 19th century ushered in unprecedented opportunities in exploiting natural resources. With the emergence of new domains in commerce and trade, the scope, frequency, and volume of financial transactions grew significantly. This particularly highlighted the inefficiency of precious metals as a practical medium of exchange. A system of government-issued paper currency backed by the gold standard was introduced to replace actual exchange of gold in regular transactions.

According to Śrīla Prabhupada—

Gold-standard currency is based on falsehood because the currency is not on a par with the reserved gold. The basic principle is falsity because currency notes are issued in value beyond that of the actual reserved gold. This artificial inflation of currency by the authorities encourages prostitution of the state economy. The price of commodities becomes artificially inflated because of bad money, or artificial currency notes. Bad money drives away good money. Instead of paper currency, actual gold coins should be used for exchange, and this will stop prostitution of gold. (SB 1.7.39, Purport)

Sure enough, gold convertibility of these paper tenders became a problem during World War I, and eventually the gold standard was fully abandoned by most countries post World War II. The Bretton Woods Conference, officially known as the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference, was held in July 1944 at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, USA.

It was a landmark gathering aimed at restructuring the global economic system after World War II. Most of the 44 participating nations agreed to peg their currencies against the US Dollar which in turn was pegged to Gold at a fixed rate. The US Dollar from then on became the reserve currency of the world economy. Soon, the growing dollar supply outpaced US gold reserves, undermining confidence in the gold peg. And in 1971, Nixon ended dollar-gold convertibility, marking the collapse of Bretton Woods and the rise of the floating fiat currency.

A key takeaway in all this is that the value peg was transitioned away from traditional stores like gold and silver, and placed squarely on national productivity and institutional strength. Unlike precious metals that carry material value, the value of fiat currencies and their stability is derived from the capability of governments and financial institutions in enabling the exploitation of the nation’s resources in an efficient and profitable manner, while encouraging consumerism on the other hand. At its core, technological prowess, resources, and energy became the key ingredients for economic growth, and the GDP became the primary benchmark for determining both a country's global standing and the perceived value of its currency.

Along with GDP, Human development is measured using indicators like education, health, and purchasing power, collectively known as the Human Development Index (HDI). However, these measures of external welfare align more closely with growth-driven narratives, rather than reflect a concern for real human development. Ironically, with these widely accepted measures of development, countries with little civilizational depth, many of which prospered on the basis of conquests and exploitation, are now considered developed. Meanwhile, countries like India, with the greatest civilizational wealth, and profound contributions to the spiritual welfare of the world, end up in the category of developing nations.

Under Western leadership, the world has become more industrious than ever, organizing itself with the singular aim of gaining mastery over nature, even to the point of commodifying humans as 'resources' as well as ‘consuming units’ in the machinery of progress. The results are evidently dehumanizing in every aspect. With respect to scientific progress Śrīla Śrīdhar Maharaja says the following wherein he particularly remarks that scientific progress objectifies everything —

Scientific progress is no progress. It is a movement in the wrong direction. It is only borrowing. It is not earning real profit at all, but rather it is like taking a loan from nature, and payment will be exacted from us to the last cent. So there is no gain, no profit, just exploitation. Science measures the circumference of the world of exploitation. Everything is objectified. We are wresting power from nature, taking a loan, but the loan must be settled, rest assured. This is not progress.

As a response to fiat currencies—issued and controlled by governments and central banks—decentralized alternatives like Bitcoin emerged, introduced by independent technology enthusiasts in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis. Unlike gold, which has tangible value, or fiat currencies backed by institutional authority, Bitcoin is entirely digital and not backed by any single entity. Instead, it operates as a decentralized ledger maintained by a global network of users. Its virtual nature and lack of central oversight make it difficult to grasp, often requiring continuous justification of its value, and leaving it highly vulnerable to market sentiment, speculation, and volatility.

As a response to fiat currencies—issued and controlled by governments and central banks—decentralized alternatives like Bitcoin emerged, introduced by independent technology enthusiasts in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis. Unlike gold, which has tangible value, or fiat currencies backed by institutional authority, Bitcoin is entirely digital and not backed by any single entity. Instead, it operates as a decentralized ledger maintained by a global network of users. Its virtual nature and lack of central oversight make it difficult to grasp, often requiring continuous justification of its value, and leaving it highly vulnerable to market sentiment, speculation, and volatility.

Riding a wave of adoption, primarily among the tech-savvy younger generation, Bitcoin has sparked an intense debate over the very concept of value. Critics, especially from the traditional financial establishment, have dismissed its legitimacy outright, comparing it to speculative bubbles like the 17th-century Dutch tulip mania [1] or labeling it a ponzi scheme [2]. In response, Bitcoin supporters have passionately defended its merit, arguing that such criticisms are outdated and misinformed. Some even question the perceived value of gold itself, pointing out that, beyond its limited industrial use, much of gold’s value comes from the way people admire and desire it, just as Bitcoin’s value arises from a collective belief.

Extending the idea of collective belief, it becomes clear that whether it's gold, fiat currency, or cryptocurrency, value is ultimately rooted in perception. Gold holds appeal because society has long admired it. Fiat currency relies on trust and fear of government authority. Bitcoin and other digital assets, meanwhile, depend on faith in technology and decentralization to preserve financial autonomy. In all three cases, value is not inherent, but constructed. And if material value is nothing more than a collective belief, then perhaps the material world itself is the most elaborate ponzi scheme ever devised, where, truly, a sucker is born every second.

Srīla Śrīdhar Mahārāja says—

The first principle of any living entity is to remain alive—that is the first principle, that should be the starting point. In the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad (1.3.28), we find:

asato mā sad gamaya tamaso mā jyotir gamaya

mṛtyor mā amṛtaṁ gamayaThis should be the primary tendency of our quest. What are these three phases? Asato mā sad gamaya—I am transient and I am impermanent. Make me eternal. Tamaso mā jyotir gamaya—I am ignorant, in nescience. Take me from ignorance to knowledge, from darkness unto light. Mṛtyor mā amṛtaṁ gamaya—I am in this mortal world, I am unhappy, unsatisfied. Take me to the plane of ānandam, enjoyment. From sorrow, misery, guide me to a fit life there. These should be the real principles of life, and any research must begin here only.

The search for true value must lead us beyond the limited confines of the material mind, into the limitless realm of pure consciousness, where the absolute value resides in the Supreme Person Śrī Kṛṣṇa—the ultimate source of all wealth, sovereignty, strength, beauty, fame, and renunciation. All movement towards Kṛṣṇa takes on an infinite character where the very concept of loss evaporates, and the value of mutual transactions of love between Kṛṣṇa and His devotees appreciates infinitely at every moment. Just as innumerable twinkling stars fade away with the rising of the sun, all other forms of wealth lose their charm when the heart is conquered by the absolute wealth, that is Kṛṣṇa.

---------

[1] The Tulip Mania was a speculative economic bubble in the Dutch Republic during the early 17th century, peaking around 1636–1637. Prices for rare tulip bulbs rose to extraordinary levels, with some bulbs reportedly worth more than a house, before the market abruptly collapsed. It is often cited as one of the first recorded financial bubbles in history.

[2] A Ponzi scheme is a form of financial fraud that lures investors with the promise of high returns, but instead of generating profits through legitimate business, it pays earlier investors using the capital of new participants. Named after Charles Ponzi, who orchestrated such a scheme in the 1920s, these schemes inevitably collapse when recruitment slows and there’s insufficient new money to sustain payouts.