Kauai, Hawaii. (CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons)

The bewildered jīva/soul, lost in the shadows and dust of Māyā’s¹ illusion, fails to perceive the true purpose of material creation. Mistaking this temporary world for a field of enjoyment and exploitation rather than a classroom for purification, it chases fleeting pleasures under the false hope of lasting fulfillment. Yet these pursuits lead only to frustration because they are nothing more than repeated attempts to find satisfaction in what has already failed us countless times before.

Everything in this world is secondhand. Trying to extract joy from matter is like picking up a piece of discarded chewing gum—already chewed, flavorless, and stale—sprinkling a little sugar on it, and expecting it to taste fresh. No matter how it's dressed up, it has already been used, drained, and discarded. Everything here has been chewed an infinite number of times.

Those constrained by the gṛha-vrata² mentality—whose only goal is bodily comfort and worldly material stability and success—are unable to recognize their true identity, the deceptive nature of matter, or the reality of Śrī Kṛṣṇa and the eternal bond they share with Him.

Modern science now echoes what the ancient sages and śāstra/scripture have long revealed: the material world is a realm of constant transformation, with nothing ever truly created or destroyed—only reshaped. The atoms that form our bodies, our food, and our surroundings—carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen—are continually recycled, flowing through air, water, soil, and the bodies of living beings in an endless cycle. The breath you take today may have passed through countless lungs before yours; the iron in your blood may once have rested deep within the earth. Yet despite this ever-shifting reality, we foolishly cling to temporary bodily identities, mistaking the changing for the permanent.

The Śrīmad Bhāgavatam (11.22.44) warns against this illusion: “The different stages of transformation of all material bodies occur just like those of the flame of a candle, the current of a river, or the fruits of a tree.” Just as a candle flickers and dims, a river flows in ever-changing patterns, or fruit ripens, sweetens, and decays, so too the body moves through inevitable stages—birth, growth, decline, and death. To identify with such a transient form is to squander the rare opportunity of human life.

It is especially tragic to see someone in old age still identifying with the body, desperately clinging to what is visibly slipping away. To equate the self with wrinkled skin, aching bones, and failing senses is not just sad; it is catastrophic. No wonder antidepressants are so often prescribed to the elderly. When meaning and identity are tethered to a deteriorating form, despair becomes unavoidable. This is a tragedy modern medicine cannot fix, because the real illness is spiritual: a deep misidentification that no pill can cure. Only by recognizing the eternal, unchanging self within—and turning toward the Supreme—can one find peace as the body fades. True intelligence lies in detaching from the illusion and anchoring oneself in what is real, lasting, and divine. And yet, despite the clarity of this truth, so many remain bound to the illusion—grasping for permanence in what was never meant to last.

Nothing in this world is truly permanent or belongs to us. All is on loan, temporarily granted for our journey through material existence. Some changes are so swift—like the clouds reshaping in the sky—that their impermanence is undeniable. Others unfold slowly, almost imperceptibly, giving the illusion of stability. A mountain will erode over centuries, a body ages and changes over decades, and a relationship may shift quietly over time, but all are subject to the same law of transformation. Like a traveler watching a cloud form and dissolve, we glance at temporary material forms—our homes, identities, possessions—and imagine they have substance and permanence. Yet what once felt unshakably real fades with time, proving to be as fleeting as vapor.

A man or woman may believe they’ve found their “true love,” pouring their hopes and identity into a partner who promises lasting happiness. And indeed, deep affection between two souls is not inherently false or wrong. But when such love is rooted solely in mutual sense gratification, disillusionment is almost inevitable. As time moves on, the very person once seen as the missing piece of one’s heart can begin to feel like a stranger. The cycle repeats—another relationship, another vow of eternal love—only to end in separation, heartbreak, or quiet resignation. Even in the rare case where a bond endures a lifetime, death inevitably severs it. What once felt unbreakable dissolves in a moment.

Yet, when a husband and wife see each other not as objects for personal enjoyment, but as fellow servants of Kṛṣṇa—meant to support one another in remembering and serving Him—their relationship is transformed. What begins as a material bond becomes a spiritual alliance, where both partners assist each other on the path of devotion. In such a purified state, the household becomes an āśrama, a sacred space centered on service. The couple becomes a team, and even ordinary life is infused with spiritual purpose. Children are not seen as extensions of the parents’ ego or tools for fulfilling worldly ambition, but as souls to be lovingly guided toward their eternal relationship with Kṛṣṇa. Love in such a home is no longer reduced to sentiment or sensuality—it becomes an offering of mutual surrender. But when this vision is absent—when Kṛṣṇa is not at the center—family life, like all material pursuits, becomes another stage for illusion. The jīva, unaware of its eternal nature, becomes entangled in chasing what can never satisfy its deepest hunger. It mistakes recycled dust for new treasure and fleeting forms for lasting refuge. Yet no arrangement of temporary matter can fulfill the soul’s yearning for permanence, purpose, and love that only Kṛṣṇa can give.

That fulfillment lies solely in connecting with our eternal source—Śrī Kṛṣṇa—who transcends the limits of time and change. He is not a drifting cloud or a vanishing mirage. He is the unchanging reality amidst a world of illusions. Only in that divine relationship does the soul find a home that does not dissolve, a love that does not fade, and a truth that does not shift with the winds of time.

śrī-prahlāda uvāca

matir na kṛṣṇe parataḥ svato vā

mitho ’bhipadyeta gṛha-vratānām

adānta-gobhir viśatāṁ tamisraṁ

punaḥ punaś carvita-carvaṇānām

“Prahlāda Mahārāja said: Because of their uncontrolled senses, persons too addicted to materialistic life make progress toward hellish conditions and repeatedly chew that which has already been chewed. Their inclinations toward Kṛṣṇa are never aroused, either by the instructions of others, by their own efforts, or by a combination of both.” (Śrīmad Bhāgavatam 7.5.30)

Material pleasure operates on a repetitive loop: desire arises, we pursue its fulfillment, and shortly after, the same craving resurfaces. Whether it’s wealth, prestige, romance, or the fleeting thrill of the next meal, we chase one experience after another, hoping that the next will satisfy us. However, like chewing sugarcane that has already been chewed or like a bee endlessly flying from flower to flower in search of one last drop of nectar, these pursuits never address the soul’s actual hunger—a hunger that can only be satisfied by spiritual food.

But there is hope for lost jīvas. The deep desire to find a permanent resting place where we can offer our love and attachment is inherent in the consciousness of every living entity. That place does exist; the sages, saints, and the Supreme Lord Himself assure us of its existence. We are guided toward Vaikuṇṭha³, the realm where no material suffering occurs.

However, without a true understanding of where that fulfillment resides and how to attain it, the soul keeps searching in mistaken ways—repeating cycles of indulgence that only deepen its hunger.

In ancient Rome, the wealthy reportedly used vomitoriums to purge their stomachs mid-feast, allowing them to return to the banquet and continue gorging—desperately chasing a pleasure that never lasted. This grotesque cycle of indulgence exposes the futility of material enjoyment: the taste of food is confined to just a few inches of the tongue and lasts only a few fleeting moments. Once swallowed, the pleasure vanishes. As the stomach fills, desire diminishes, revealing the temporary and diminishing nature of sensual gratification. The Romans’ attempts to restart the cycle through forced purging only exposed a deeper emptiness—an inner void that no amount of indulgence could ever fill. In the same way, the jīva becomes trapped in the fire of kāma, or lust—an unrelenting thirst that only intensifies the more we try to satisfy it. Trying to extinguish kāma through indulgence is like pouring gasoline on a blaze: the more we feed it, the more it consumes us, leaving us scorched, hollow, and thirstier than before.

In Bhagavad-gītā (2.62-63) Sri Krishna explains how repeated indulgence in the senses leads only to deeper bondage:

saṅgāt sañjāyate kāmaḥ

kāmāt krodho ’bhijāyate

krodhād bhavati sammohaḥ

sammohāt smṛti-vibhramaḥ

smṛti-bhraṁśād buddhi-nāśo

buddhi-nāśāt praṇaśyati”

“While contemplating the objects of the senses, a person develops attachment for them, and from such attachment lust develops, and from lust anger arises. From anger, complete delusion arises, and from delusion bewilderment of memory. When memory is bewildered, intelligence is lost, and when intelligence is lost one falls down again into the material pool."

We’ve all witnessed someone explode with anger over something seemingly minor or inconsequential. And if we’re honest, we’ve likely done the same—reacting intensely to a small irritation as if it were a great offense. But the wise understand that the visible trigger is rarely the true cause. Beneath the outburst lies a deeper unrest—an unfulfilled longing, or a desire once indulged that left us unsatisfied. This quiet frustration accumulates over time, buried beneath the surface, waiting for the slightest excuse to erupt.

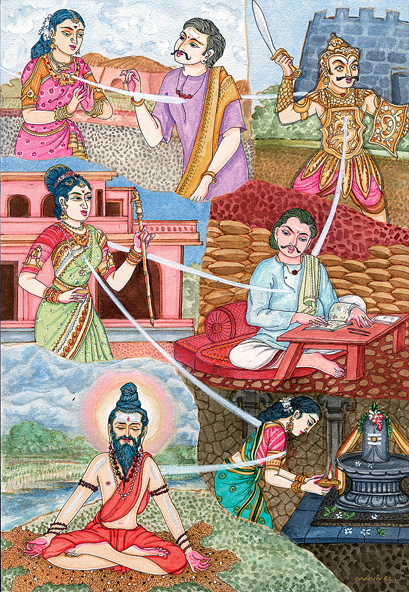

Figures from Vedic history—such as Hiraṇyakaśipu and Rāvaṇa—embody this cycle of chewing the chewed: again and again. They pursued fleeting pleasures, only to be left unsatisfied and eventually defeated. Hiraṇyakaśipu sought to conquer and dominate, driven by an insatiable thirst for power and control. Engaging the material senses in their objects he became more and more frustrated and angry. Even after performing severe austerities and receiving boons from Lord Brahmā that made him nearly invincible, he could not control his unquenched desire, repeatedly seeking to destroy Krishnas devotees and to impose his will on the universe. Although he had every imaginable object of sense gratification his indulgences left him hollow and angry. His anger only grew stronger over time—like a fire stoked by his own frustrations—consuming his heart and blinding him to the inevitable consequences of his actions.

Similarly, Rāvaṇa endlessly indulged in his lust and pride. Despite his unmatched wealth, a kingdom of gold, and the submission of his subjects, he craved what he could not have—Mother Sītā, the devoted consort of the Supreme Lord Rāma, who embodies all pure feminine qualities, such as faithfulness, chastity, purity, and virtue. His repeated abductions of celestial women, culminating in his final attempt to seize Sītā, reveal a man trapped in a self-destructive cycle of desire. These stories serve as powerful warnings, exposing the emptiness of pursuing material goals and pleasures repeatedly, no matter how grand, alluring, and intoxicating they may seem.

Just as Rāvaṇa’s insatiable cravings led to his downfall, this same pattern unfolds today, merely dressed in the garments of so-called modern life.

Modern society mirrors what Vedic history recorded. Contemporary culture thrives on constant consumption and novelty: new gadgets, new relationships, new experiences. We are captivated by the latest bells and whistles on smartphones or computers that appeal to our senses, only to find they become outdated once new models flood the market shortly afterward. Once again, we are told that the latest edition will bring us happiness. However, beneath the allure of novelty, the same old pattern returns. What is celebrated today is discarded tomorrow, leaving the soul restless and unfulfilled.

As this relentless pursuit of novelty fails to satisfy the heart, society starts to redefine meaning itself, altering not only preferences but also moral principles.

The collapse of moral boundaries has led society into increasingly dangerous and uncharted territory. Behaviors once universally recognized—across civilizations and sacred traditions—as destructive to personal integrity and societal health are now being normalized, glamorized, and protected by law. In this upside-down world, actions long deemed immoral are now exalted as virtues.

However, the abandonment of moral restraint is not a sign of progress or liberation—it signifies the deepening of the soul’s bondage to illusion. True freedom is not about having the license to act on every impulse but about having the strength to rise above them through spiritual discipline and higher understanding. When lust is left unchecked, it does not stay dormant; it grows like a fire fed by wind, consuming clarity, virtue, and peace, and pulling the jīva deeper into layers of agitation, corruption, and despair. History shows us this decline clearly. With each passing decade, public displays of depravity become bolder. What was once hidden in shame is now displayed openly—on social media, in music and movies, and even inside classrooms. In the name of progress, society celebrates its own decay, as the obscene becomes trendy and the unthinkable becomes normal, rushing the culture headlong into a spectacle of spiritual ruin.

“parācāḥ kāmān anuyanti bālāḥ, te mṛtyor yanti vitatasya pāśam”

"Foolish persons pursue outward pleasures and thus enter into the wide-spread snare of death.” (Kaṭha Upaniṣad)

The more one seeks fulfillment through the external senses, the more entangled one becomes in the very suffering one longs to escape.

But to break free from this entanglement, one must first understand who they truly are—beyond the body, the mind, and the flickering desires of the senses.

Jīva-tattva⁵, the ontological truth of the self, is revealed in the Vedic scriptures. The root of the jīva’s misfortune lies in its misidentification with matter, mistaking the temporary body, restless mind, and shifting desires for the self. In Gauḍīya Vedānta, the jīva is described as nitya-jīva—an eternal, indivisible, conscious spark, distinct from both gross and subtle material elements. This foundational truth is affirmed in the Śrīmad Bhāgavatam and other Vedic texts. The truly learned, who have realized the Absolute, do not merely theorize but know through direct experience that the soul is completely separate from the physical and mental coverings. This is not an abstract idea but a lived realization—awakening to the jīva’s eternal, spiritual nature and its unbreakable connection with the Supreme Lord.

This understanding forms the very foundation upon which the distinction between the individual soul and the Supreme Soul is built.

The Kaṭha Upaniṣad (2.2.13) clarifies this distinction: nityo nityānāṁ cetanaś cetanānām—“Among all eternal beings, there is One who is the eternal Supreme, and among all conscious beings, there is One who is supremely conscious.”

This profound verse dismantles the misconception of absolute monism. It delineates that while there are countless eternal, conscious entities (nityānām cetanānām), there is One (nityaḥ, cetanaḥ) who is categorically supreme—unlimited, omniscient, and the ultimate source and sustainer of all others. The jīva is never the complete whole, never the Absolute; it is an infinitesimal spark of the infinite fire—qualitatively one with the Supreme, but quantitatively distinct.

The jīva, a product of the taṭasthā-śakti—Kṛṣṇa’s marginal energy—is positioned between the spiritual and material realms, able to turn toward either. It is inherently spiritual but vulnerable to illusion when it turns away from Kṛṣṇa. By misidentifying with matter, it forgets its true nature; however, by returning to Him, it reawakens its identity as His eternal servant. This intermediate position explains both the soul’s greatness—its eternal, spiritual nature—and its weakness—its tendency to fall into ignorance.

Just as a spark emanating from a fire can never be the whole thing, or as a drop of ocean water can never be the entire ocean, the jīva is eternally of the same nature as God, but never becomes God. The jīva is a dependent being (aṇu-caitanya), whereas the Lord is the independent, all-pervading supreme consciousness (vibhu-caitanya). This eternal difference in magnitude and potency is the basis for the eternal relationship of service: the jīva’s inherent identity is as the servant (dāsa) of the Supreme Person. But being in ignorance of her constitutional position, the jīva comes under the sway of māyā and becomes entangled in the cycle of birth and death, seeking fulfillment in that which can never satisfy.

yasyātma-buddhiḥ kuṇape tri-dhātuke

sva-dhīḥ kalatrādiṣu bhauma ijya-dhīḥ

yat tīrtha-buddhiḥ salile na karhicij

janeṣv abhijñeṣu sa eva go-kharaḥ

“One who identifies his self as the inert body composed of mucus, bile and air, who assumes his wife and family are permanently his own, who thinks an earthen image or the land of his birth is worshipable, or who sees a place of pilgrimage as merely the water there, but who never identifies himself with, feels kinship with, worships or even visits those who are wise in spiritual truth — such a person is no better than a cow or an ass.” (Śrīmad Bhāgavatam 10.84.13)

The alignment between ancient revelation and modern scientific observation underscores a universal truth: the body is not a fixed identity, but a fleeting construct—constantly dissolving and reforming—making it an unfit foundation for defining the self.

Modern science supports this insight by revealing the transient and ever-changing nature of not only the human body but all physical forms. What we perceive as a stable, enduring structure is, in fact, in a constant state of flux. Every atom and cell in the body is replaced over time. The skin renews itself approximately every 2 to 4 weeks. The liver regenerates in about 5 months. The lining of the stomach is replaced in under a week, and even red blood cells are typically renewed every 3 to 4 months.

Organs like the heart and brain, which contain some of the body’s longest-living cells, are not exempt from the body’s ongoing biochemical renewal. While many neurons in the brain do not divide or replicate after early development, the atoms and molecules that make up those cells are gradually replaced over time through metabolic processes. This means the brain is in a constant state of molecular turnover, even if the cells themselves remain. Some estimates suggest that the molecular components of the brain may be largely renewed within about a year. The molecular composition of the brain is renewing itself moment by moment.

In fact, scientists estimate that the body you have today is not the same one you had 7 to 10 years ago; all the matter—every molecule and atom—has changed. Though some structures persist longer than others, the building blocks are always being recycled.

This ever-shifting organism we identify with—our so-called self—is in truth just a flowing current of impermanent material elements. And yet the jīva—unchanging, sentient, and eternal—mistakes this temporary aggregate of elements as the self. This fundamental illusion, perpetuated by bodily identification, is the seed of endless suffering, not only on a personal level but on a global scale. From this root error arise countless false identities: “I am Black,” “I am White,” “I am American,” “I am Mexican,” “I am male,” “I am female,” “I am a farmer,” “I am a day trader,” “I am a president,” “I am a king,” “I am Christian,” “I am Hindu,” “I am Muslim.” These false identities—based on race, nationality, gender, religion, occupation, or social status—are all temporary constructs tied to the body, which itself is constantly changing and destined to perish. In contrast, sanātana-dharma—the eternal function of the soul—is not defined by external designations, but by our unchanging identity as loving servants of the Supreme, Śrī Kṛṣṇa.

Mistaking these fleeting labels for the essence of who we are fuels pride, division, and conflict. It turns superficial differences—such as gender, age, race, nationality, and social standing—into causes for hatred, discrimination, and war. Men pit themselves against women, one generation ridicules another—youth branding elders as out of touch, while elders condemn youth. Nations clash, not out of truth or principle, but due to the illusion of superiority tied to birth and border. “I am American,” “I am Russian,” “I am Chinese,” “I am Palestinian,” “I am an Israeli”—these designations are repeated again and again, as entire populations define their worth and purpose by them.

These are merely temporary bodily identities, bound to the fleeting circumstances of one brief human life. In the next, the same soul may be born into an entirely different race, nation, or religion—the oppressor becoming the oppressed, the persecutor reborn among those he once reviled. Such is the exacting justice of karma, which teaches through lived experience. Yet despite this, humanity clings to illusion, waging wars and igniting revolutions over transient labels rooted in bodily misidentification. When the eternal self is ignorant of its divine origin and falsely identifies with the body, even the most trivial differences become causes for hatred. But true resolution lies not in stripping away these labels alone, but in awakening to our eternal identity—not as masters, but as servants of Śrī Kṛṣṇa. The jīva’s innate drive to serve finds its perfection only when offered to its original source. Until we transcend false designations and engage in loving devotional service, conflict will persist—its forms ever-changing, but its root unchanged.

This inevitable cycle of turmoil and impermanence eventually forces the sincere seeker to look beyond the surface, stirring a deeper inquiry into the self and the source of lasting truth.

Eventually, the illusion begins to crack—as everything we once depended on shifts or disappears—prompting the awakened soul to ask: What endures when all else changes? Who am I, really? Though the body and mind undergo constant transformation, the conscious witness remains unchanged. Kṛṣṇa affirms this in the Bhagavad-gītā (2.13): “Just as the embodied soul continually passes in this body from boyhood to youth to old age, the soul similarly passes into another body at death. A sober person is not bewildered by such a change.” He further explains that the jīva is His parā-prakṛti—superior energy—distinct from the material elements of earth, water, fire, air, ether, mind, intelligence, and false ego (Gītā 7.4–5). Recognizing this eternal identity as a conscious spark of Kṛṣṇa’s own potency marks the beginning of real freedom.

What a gross misuse of the precious human form it is to spend a lifetime without realizing ones eternal nature. Wasting this rare opportunity by remaining trapped in an illusion is a tragic mistake. Human life is a rare and temporary gift, perfectly suited for self-realization. There’s no guarantee of receiving another human birth for many lifetimes if this life isn’t used for its true purpose. If this chance is missed, the soul may wander again through lower forms of life, unable to question, reflect, or transcend the real issues of life—birth, death, old age, and disease. Missing this window of awakening isn’t just a misfortune; it’s a serious mistake with far-reaching consequences.

“After many, many births and deaths one achieves the rare human form of life, which, although temporary, affords one the opportunity to attain the highest perfection. Thus a sober human being should quickly endeavor for the ultimate perfection of life as long as his body, which is always subject to death, has not fallen down and died. After all, sense gratification is available even in the most abominable species of life, whereas Kṛṣṇa consciousness is possible only for a human being.” Srimad Bhagavatam 11.9.29

Instead of using this rare human birth to transcend illusion and awaken to the soul’s eternal identity, many tragically waste it by reinforcing that very illusion, elevating temporary bodily designations into false ideologies. What begins as a fleeting identity tied to the body soon calcifies into rigid ideology, and when divorced from spiritual truth, such ideology inevitably breeds fanaticism. False labels become banners, and the external—race, gender, nation, status—is falsely made absolute. In clinging to these illusions, the jīva drifts further from its true self, drowning in the very darkness it was meant to escape.

We see this clearly in many of today’s activist movements across the world, where a shallow understanding of identity and fairness prevails—one that makes no reference to the eternal soul or the divine law of karma. Lacking these essential spiritual foundations, such activism—though often presented as compassionate and even rooted in good intentions—inevitably intensifies the very divisions it claims to heal, further entangling society in conflict, resentment, and illusion.

True peace and harmony within society will never be achieved through political slogans, social revolutions, or any man-made ideology that denies the soul’s divine origin. No-ism—whether it be nationalism, communist socialism, capitalism, or woke progressivism—can heal the heart of humanity. Peace will come only when mankind awakens to its true spiritual nature: not as masters or victims of this world, but as eternal servants of the Supreme Lord. It is only through this realization that unity becomes possible—not the superficial unity of external sameness, but the deep harmony that arises when one sees all beings as fellow servants of the Supreme Personality of Godhead, regardless of external designations.

This awakening is not the product of any fanatical ideology, but of deep spiritual realization that comes only after lifetimes of searching, struggle, and disillusionment with the material world.

bahūnāṁ janmanām ante

jñānavān māṁ prapadyate

vāsudevaḥ sarvam iti

sa mahātmā su-durlabhaḥ

—Bhagavad-gītā 7.19

“After many births and deaths, he who is actually in knowledge surrenders unto Me, knowing Me to be the cause of all causes and all that is. Such a great soul is very rare.”

Like a lost child searching for home in a foreign land, the soul restlessly seeks fulfillment in the external world, never realizing that its true nature is to serve and love the Supreme Person. Even a successful family man—who thinks he has secured his home and his family through wealth and social standing—must eventually confront the limits of his power. Despite his best efforts, he cannot protect his loved ones from the inexorable cycle of repeated birth and death.

The Śrīmad Bhāgavatam warns:

gurur na sa syāt sva-jano na sa syāt

pitā na sa syāj jananī na sā syāt

daivaṁ na tat syān na patiś ca sa syān

na mocayed yaḥ samupeta-mṛtyum

"One should not become a guru, a father, a mother, a demigod, or a husband if one cannot deliver his dependents from the cycle of birth and death.” —Śrīmad Bhāgavatam 5.5.18

This powerful injunction underscores the grave responsibility of guidance because, without true spiritual direction, the soul remains entangled in delusion, mistaking suffering for pleasure.

In the Śrīmad Bhāgavatam (2.3.19, purport), Śrīla A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Mahārāja vividly describes how the camel, in its pursuit of satisfaction, chews thorny twigs that injure its tongue and mouth lining, yet it mistakes the taste of its own blood for sweetness. Śrīla Prabhupāda writes:

"The camel also sucks its own blood while chewing thorny twigs. The thorns the camel eats cut the tongue of the camel, and so blood begins to flow within the camel's mouth. The thorns, mixed with fresh blood, create a taste for the foolish camel, and so he enjoys the thorn-eating business with false pleasure."

The camel’s mouth lacks nerve endings sensitive enough to feel the pain of its cuts, so it keeps chewing the thorns, unaware that its supposed pleasure is really just self-inflicted harm. The camel relishes the taste of its own blood. Similarly, the jīva, driven by material desires, endlessly chases sensory pleasure, failing to realize that these pursuits only lead to more suffering. Under Māyā's influence, what is pursued to lessen suffering becomes the source of that suffering.

Tragically, the jīva wanders in a foreign land, estranged from its true home, mistaking pain for pleasure and exile for belonging—yet all the while, the Lord is searching for His lost servant.

As Śrīla B.R. Śrīdhara Mahārāja states:

"We are quarreling in a foreign land for fictitious gain. But Kṛṣṇa is engaged in a loving search for His long lost servants."

He further explains:

"When we are in a foreign land, we may seek the comforts which are supplied in hotels, but when we reach home, the hotel comforts are discarded; we find no more use for them. Sometimes a minor is kidnapped from home. Later, while visiting his native place he may stay in a hotel, but if he suddenly finds his father's house, and returns home, his parents will recognize him and say, 'O, my son! You were stolen from us when you were young. We recognize your face. I am your mother, this is your father, here is your sister.' Then the hotel is no longer needed. In a similar way, with the inner awakenment of the soul, when we return back home, back to Godhead, we will find our comfortable home with Kṛṣṇa."

—Śrī Guru and His Grace

The jīva—the eternal, individual unit of consciousness—journeys through countless lifetimes, riding upon the chariot of the material body, endlessly searching for a sense of belonging, a place to call “home.” But this quest is tragically misdirected. Just as it would be absurd for a traveler in transit to mistake the airport terminal for his final destination—rearranging the furniture, bonding with fellow passengers, and calling the lounge his residence—the soul, under the powerful illusion of Māyā, mistakes the temporary body and world for its true identity and home. No rational traveler would invest fully in a layover, yet the jīva builds its entire sense of self around that which it must abandon sooner or later.

In the Vedic scriptures, this world is known as mṛtyu-loka⁷—the realm of death. From the highest planet to the lowest, all places within this material universe are subject to destruction and decay.

As Kṛṣṇa declares in the Bhagavad-gītā (8.16): “From the highest planet in the material world down to the lowest, all are places of misery wherein repeated birth and death take place. But one who attains My abode never takes birth again.”

The jīva, though eternal by nature, is caught in a revolving door of embodiments, each one destined to perish. No matter how refined or opulent one’s temporary situation may appear, it cannot escape this universal truth. Thus, to anchor our identity in the perishable is to guarantee sorrow. True wisdom begins when one recognizes that this world is not our permanent home, but a transit zone—meant to be passed through, not clung to.

Death is always close by, yet the jīva thinks she will live forever in the false world she inhabits. As Yamarāja, the lord of death, states in the Mahābhārata: “Day after day, countless living beings go to the abode of death, yet those who remain aspire for permanence thinking they will never die. What could be more astonishing than this?” And as Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura poetically writes, “Life is unsteady and flickering, like a drop of water on a lotus petal.” In this illusion, the soul forfeits the opportunity to reach her actual destination: the spiritual realm of Vaikuṇṭha, where her true nature—sat-cit-ānanda⁶—is fully awakened and realized.

This forgetfulness of our true identity lies at the heart of the modern obsession with wellness. Practices such as yoga exercises, clean eating, mindfulness, detox routines, and the like may promote physical health and mental clarity, and can certainly be recommended for overall well-being. Yet their underlying aim remains largely the same: to enhance one’s enjoyment within the material world. As such, they ultimately fall short. No matter how refined, these practices cannot lead to self-realization remaining on the material platform. When the pursuit of wellness becomes an end in itself it only reinforces deeper illusion that fulfillment can be found in the ever changing scenery of the material world an illusion that underlies all forms of misplaced attachment.

This is the tragic absurdity of misdirected attachment: the soul, lost in spiritual amnesia, mistakes the material world for its home and clings to fleeting roles, relationships, and possessions, hoping they will provide lasting fulfillment. Like a traveler mistaking the airport terminal for his destination, the jīva invests its heart in what was only ever a temporary layover. But time, the great destroyer, inevitably strips everything away: bodies decay, loved ones part, fortunes fade, and even the most accomplished materialist is torn from all he owns at death. Everything crumbles because none of it was meant to last.

The material world is a perilous place, fraught with uncertainty at every turn. As Śukadeva Gosvāmī warns King Parīkṣit, “padaṁ padaṁ yad vipadāṁ na teṣām”—there is danger at every step. No amount of wealth, intelligence, or social standing can shield one from the unpredictable blows of fate: disease, natural disaster, betrayal, heartbreak, or death. Even the most carefully constructed life can unravel in an instant. The wise see this instability not with paranoia, but with spiritual clarity. They recognize that real safety lies not in external arrangements but in taking shelter of the lotus feet of the Lord, who alone offers protection that is infallible and eternal.

Ignorance of our true identity and eternal home traps us in the futile cycle of “chewing the chewed,” endlessly reliving the same disappointments in new forms. No amount of material success can break this cycle, for true fulfillment lies beyond the reach of wealth, power, or influence. Only by the mercy of a realized spiritual guide—who lifts the veil of illusion and reveals our real identity as eternal servants of the Supreme—can we return to our true home, the spiritual world, where the soul’s deepest longing for love, shelter, and lasting happiness is finally fulfilled.

What the jīva truly craves is an infinite ocean of bliss—an endless wellspring of ānanda/spiritual happiness that alone can satisfy its boundless nature. That infinite ocean is found only in the relationship with Kṛṣṇa, the source of all happiness and the supreme object of love. Krishna is the only one who can fill us up. Trying to satisfy the soul’s thirst by engaging the senses in repeated, temporary pursuits is futile, like attempting to fill the ocean with a drop of water. Only by immersing oneself in the service of Kṛṣṇa can the jīva find real and lasting fulfillment.

Māyā, the divine illusory energy, expertly reshapes the same old matter to appear fresh and enticing. Through the constant play of māyā, what has been endlessly chewed seems, once again, sweet and full of promise. Śrīmad Bhāgavatam (11.10.23) describes how the mind remains attached to these shifting forms.

na te viduḥ svārtha-gatiṁ hi viṣṇuṁ

durāśayā ye bahir-artha-māninaḥ

andhā yathāndhair upanīyamānās

te ’pīśa-tantryām uru-dāmni baddhāḥ

“Persons who are strongly entrapped by the consciousness of enjoying material life, and who have therefore accepted as their leader or guru a similar blind man attached to external sense objects, cannot understand that the goal of life is to return home, back to Godhead, and engage in the service of Lord Viṣṇu/Krsna. As blind men guided by another blind man miss the right path and fall into a ditch, materially attached men led by another materially attached man are bound by the ropes of fruitive labor, which are made of very strong cords, and they continue again and again in materialistic life, suffering the threefold miseries.”

True relief comes not from more chewing, but from awakening to the soul’s eternal nature. In the path of bhakti, or loving devotional service, one discovers a higher taste that eclipses the fleeting sweetness of material enjoyment. As Śrīmad Bhāgavatam (1.2.19) affirms:

tadā rajas-tamo-bhāvāḥ

kāma-lobhādayaś ca ye

ceta etair anāviddhaṁ

sthitaṁ sattve prasīdati

“As soon as irrevocable loving service is established in the heart, the effects of nature’s modes of passion and ignorance, such as lust, desire and hankering, disappear from the heart. Then the devotee is established in goodness, and he becomes completely happy.”

This higher taste and spiritual nourishment satisfy the soul at its core, loosening the grip of material desires and revealing a realm of eternal and vibrant fulfillment.

In conclusion, the metaphor of “chewing the chewed” is a profound insight into the nature of the material world: everything is recycled, everything has already been experienced, and no amount of external novelty can fill the soul’s inner emptiness. The scriptures and the lives of the sages and saints consistently remind us that real happiness is not found in temporary pleasures or achievements, but in realizing our eternal identity as servants and lovers of the Supreme Lord Sri Krishna.

Glossary

¹ Māyā – The divine illusory energy of the Lord that bewilders the living entities (jīvas), keeping them in ignorance of their true spiritual identity and eternal relationship with Kṛṣṇa. In popular theology—especially within certain Western traditions—it is often said that God created the world for humanity’s enjoyment as a paradise, but that Satan entered the picture and ruined it. However, this dualistic notion misrepresents the deeper spiritual reality as revealed in the Veda. Māyādevi (or Satan, in other languages) is not an autonomous being acting in opposition to God. Māyādevī is a servant of Kṛṣṇa, fully under His control, executing His will with precision and purpose.

The material world was not created for our enjoyment, but it is arranged to appear that way—as a stage for the jīva’s attempt to enjoy separately from God. Because the jiva rebels against the Supreme Lord it desires to usurp the position of God as the enjoyer. In truth, this world is a reformative facility, not a playground for the soul. Built into this divine arrangement is a perfect system of cause and effect/karma that gradually purifies the soul’s misguided desire to be the enjoyer, the imitator of God. Māyā’s purpose is to exhaust the soul’s material hopes and turn it back toward its rightful position—as the humble servant and lover of the Supreme Person.

As Lord Kṛṣṇa declares in the Bhagavad-gītā (7.14), “This divine energy of Mine, consisting of the three modes of material nature, is difficult to overcome. But those who surrender unto Me can easily cross beyond it.”

One cannot serve two masters. As long as the jīva resists surrender to Kṛṣṇa, it will, by default, serve Māyā. To serve Māyā is to be bound by illusion; to serve Kṛṣṇa is to be free. This is the inescapable spiritual law: one will either serve God or serve illusion/Māyā there is no middle ground. Yet even Māyādevī, in her formidable role, is ultimately working for our deliverance. When the soul sincerely turns back toward Kṛṣṇa and serves Him purely, Māyādevī steps aside, having fulfilled her sacred duty.

² Gṛhavrata (गृहव्रत) —One who is attached to living in a comfortable home although it is actually miserable; one attached to the material duties of family life.

³ Vaikuṇṭha — literally “free from anxiety”—refers to the eternal, spiritual abode of the Lord where there is no birth, death, old age disease or material change. Unlike the ever-mutating material realm, Vaikuṇṭha is a plane of pure existence, knowledge, and bliss (sat-cit-ānanda), as described in the Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam and other Vedic texts.

⁴ Kāma — in Sanskrit, kāma refers to material desire or lust, particularly the selfish drive for sensual and emotional gratification. While it can also mean love in general contexts, in Vaishnava philosophy kāma is seen as one of the primary enemies of the soul, binding the living entity to the cycle of birth and death (saṁsāra) when not transformed into pure, selfless devotion (prema).

⁵ Jīva-tattva — The Vedic truth concerning the soul. The jīva is the eternal, conscious entity distinct from both the gross and subtle bodies. It is not a temporary product of material nature but a fragmental part (aṁśa) of the Supreme Lord (Gītā 15.7), always dependent and never the complete whole. According to the Kaṭha Upaniṣad (2.2.13), “nityo nityānāṁ cetanaś cetanānām”—“Among all eternal beings there is One who is supremely eternal, and among all conscious beings there is One who is supremely conscious.” This emphasizes the ontological distinction between the finite jīvas and the infinite Supreme Being. The jīva is never God, but an infinitesimal spark, meant for loving service, not for independent enjoyment.

⁶ Sat-cit-ānanda (सच्चिदानन्द) — The eternal, blissful, and conscious nature of the pure self. The jīva, in its pure state, is not material but spiritual, possessing eternity (sat), full knowledge (cit), and bliss (ānanda). This contrasts starkly with the false self, which is bound by temporality, ignorance, and suffering. When identified with the body and mind, the soul experiences fragmentation, fear, and lack. But when the jīva awakens to its true nature and establishes its relationship with the Supreme Lord, it regains its original, joyful condition as a conscious servant of the Supreme Personality of Godhead, Lord Sri Krsna.

⁷ Mṛtyu-loka (मृत्युलोक) — A Sanskrit term meaning “the realm of death,” used in the Vedic scriptures to describe the entire material world, including even the highest heavenly planets. The root word mṛtyu means “death,” and loka means “planet” or “realm.”

This classification underscores the fundamental nature of material existence: impermanence and suffering. No matter how refined, beautiful, or long-lasting a situation may appear—whether on Earth or in the higher realms—it is still under the jurisdiction of time and destined for destruction. All those who take birth here must also die.

In contrast, the spiritual world, such as Vaikuṇṭha or Goloka, is amṛta-loka—the realm of immortality—where no death, decay, or rebirth exists. The designation mṛtyu-loka serves as a sobering reminder that the material world is not our true home, but a temporary stop on the jīva’s journey, meant to encourage renunciation and the pursuit of liberation through devotion (bhakti).