Our recent pilgrimage to the Himalayan shrines of Uttarānchal was more than a journey through stunning landscapes—It was a walk through a sacred history. These mountains have long been home to sages, scriptures, and the Lord's pastimes. As we traversed the paths once taken by great saints, we could feel the spiritual foundation of India all around us.

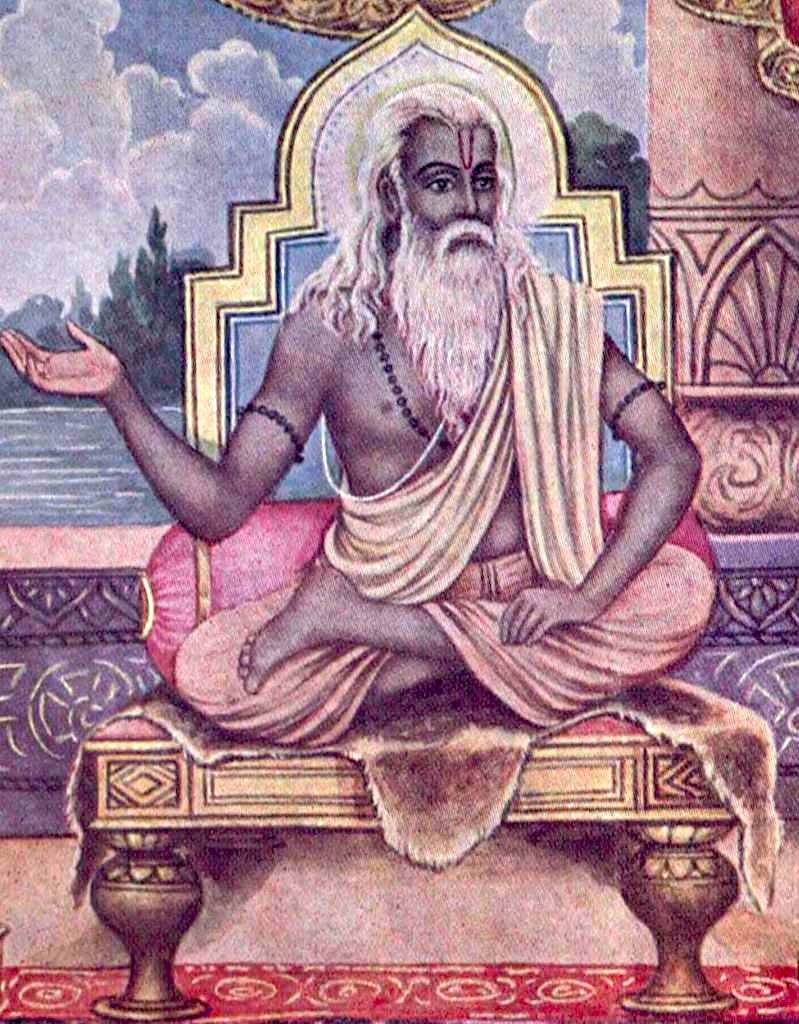

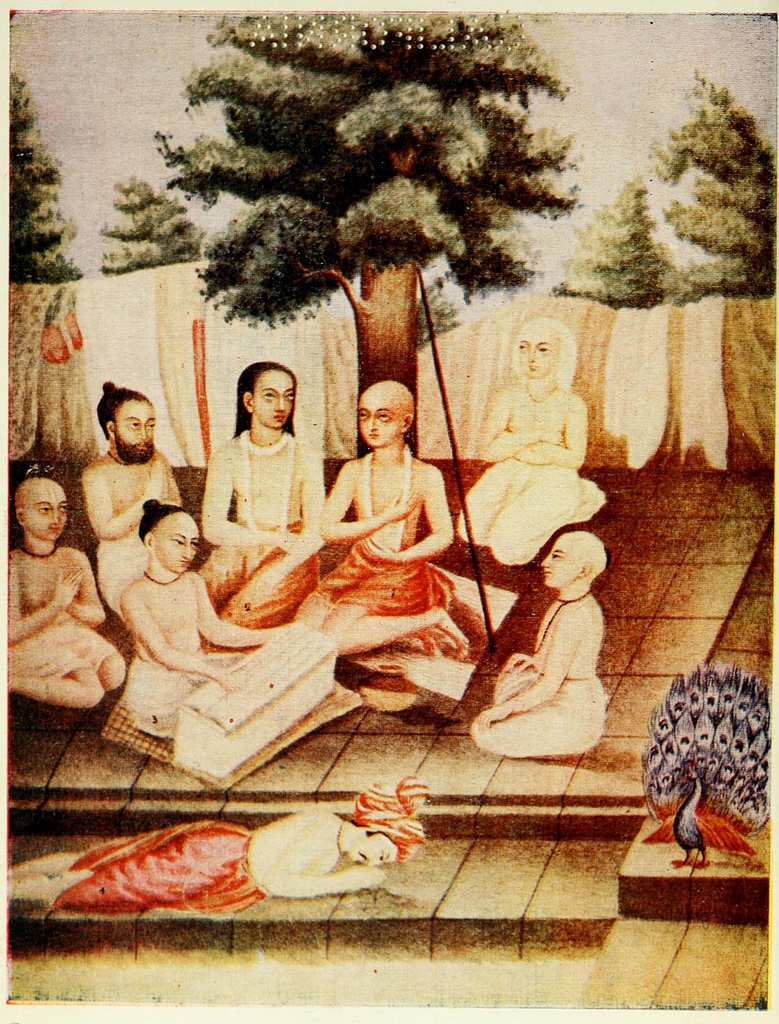

Among the most significant of these sages is Śrī Vyāsadeva, who is credited with compiling the ancient Vedic scriptures that continues to guide us even today. The Vedic literatures are considered to be apauruśeya which means they are unauthored, or not produced by any individual under the modes of the material nature. Their existence is in eternity in the form of essential knowledge of the absolute truth. Śrī Vyāsadeva who is the literary incarnation of Lord Viṣṇu revealed the Vedas in their literary form and compiled them into four divisions—Ṛk, Yajur, Sāma, and Atharva, along with other related literatures like the puraṇās, and the Mahābhārata.

vyāsāya viṣṇu rūpāya vyāsa rūpāya viṣṇave

namo vai braḥma nidhaye vāsiṣṭhāya namo namaḥ

Salutations to Vyāsa in the form of Viṣṇu and Viṣṇu in the form of Vyāsa, and to the one who is the treasure house of the Vedas. Salutations to the one born in the noble family of Vasiṣṭha. (Viṣṇu Sahasranāma, 4)

Śrī Vyāsadeva is considered to be one of the seven ciranjeevi’s [1], endowed with practically an eternal lifetime in this world, and can still be seen with a divine vision. It is said that he composed the Vedic śāstras near Badarīkāśrama in the Himalayan region. In the words of Śrīla Śrīdhar Mahārāja, “Revealed truth in different forms, in their greatest magnitude and detail was given by Vyāsadeva here, from Badarikāśrama.” About five kilometers north of Badrinath lies the village of Māṇā, where Vyāsadeva is believed to have resided in a cave while performing his literary work. The Saraswati river, also known as the gupta-gāmini (one that flows secretly), emerges in the nearby area, before it disappears underground.

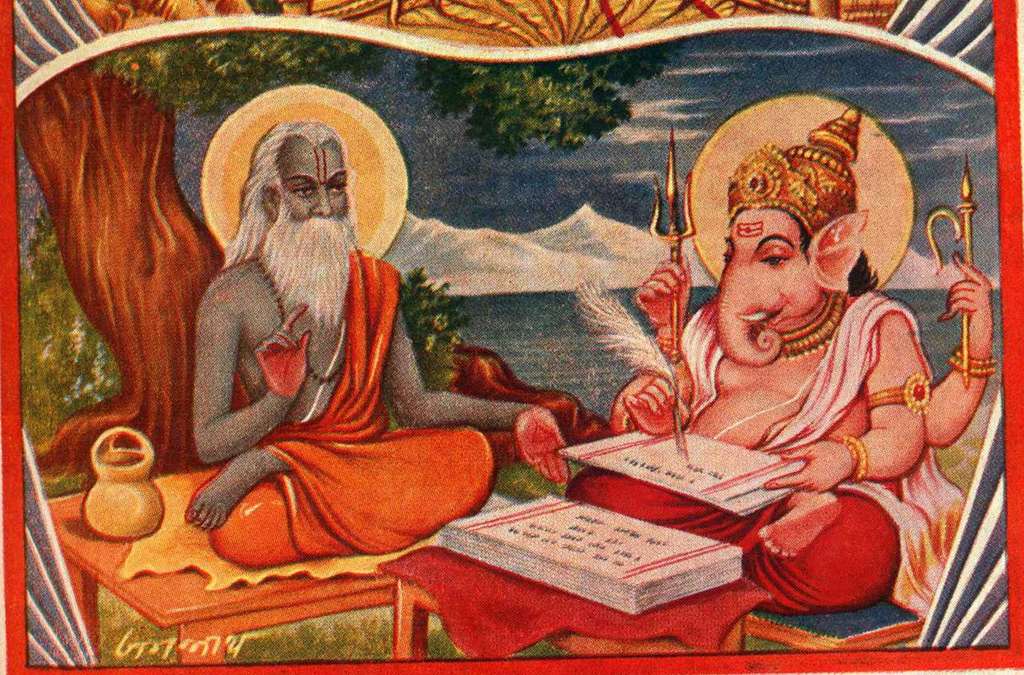

The area surrounding Badrinath holds great significance, being mentioned frequently in Vedic texts that recount important pastimes of the Lord and His devotees. Primarily, Badrinath is known as the place where Nara-Nārāyaṇa, a pair of sages considered as incarnations of Lord Viṣṇu, performed their great penance. Vyāsadeva’s cave (Vyāsa-gufa) remains a revered pilgrimage site, held sacred for its profound history. It was here that Śrī Vyāsadeva collaborated with Gaṇeśa, who served as his scribe in composing the epic Mahābhārata. In undertaking the monumental task of composing the epic, Vyāsadeva needed someone capable of writing at the speed of thought. Gaṇeśa, fully qualified for such a task, agreed to assist on the condition that Vyāsadeva would not pause in his dictation. According to a popular legend, during the writing of the Mahābhārata, Gaṇeśa’s pen broke, and without hesitation, he broke off his left tusk to use as a pen to continue the work.

Even after writing the bulk of the Vedic texts for the upliftment of humanity, Śrī Vyāsadeva remained dissatisfied, and was unable to understand the cause of his unease. At this crucial juncture Śrī Nārada Muni appeared at Vyāsadeva’s place and imparted several vital instructions that led to the writing of the eighteenth purāṇa, Śrīmad Bhāgavatam, which is also the final and the most important literary work of Śrī Vedavyāsa, that reveals the pastimes and the glories of Bhagavān Śrī Kṛṣṇa. In His strong criticism of Śrī Vedavyāsa, Śrī Nārada Muni spoke the following specifically with respect to the material rewards promised in the karmakānḍa—

jugupsitaṁ dharma-kṛte 'nuśāsataḥ svabhāva-raktasya mahān vyatikramaḥ

yad-vākyato dharma itītaraḥ sthito na manyate tasya nivāraṇaṁ janaḥ

vicakṣaṇo 'syārhati vedituṁ vibhor ananta-pārasya nivṛttitaḥ sukham

pravartamānasya guṇair anātmanas tato bhavān darśaya ceṣṭitaṁ vibhoḥ

The people in general are naturally inclined to enjoy, and you have encouraged them in that way in the name of religion. This is verily condemned and is quite unreasonable. Because they are guided under your instructions, they will accept such activities in the name of religion and will hardly care for prohibitions.

The Supreme Lord is unlimited. Only a very expert personality, retired from the activities of material happiness, deserves to understand this knowledge of spiritual values. Therefore those who are not so well situated, due to material attachment, should be shown the ways of transcendental realization, by Your Goodness, through descriptions of the transcendental activities of the Supreme Lord. (SB 1.5.15-16)

Śrī Vedavyāsa meditated upon Śrī Narada’s instructions and eventually composed the Śrīmad Bhāgavatam. Śrīla Śrīdhar Mahārāja describes the events that followed—

Vyāsadeva thought that mokṣa — the brahma-jñāna (liberation in the non-differentiated Absolute) — had been given the highest position. Now, the higher conception revealed to me by Devarṣi Nārada must be delivered to the world by a person whose brahma-jñāna is unquestionably admitted by all the scholars. So he searched for Śukadeva thinking, “Śukadeva is the only person who is very widely respected by the so-called liberationists. This higher doctrine should be brought to light through him, and then the position of Bhāgavatam will be automatically unchallengeable.”

Śukadeva Goswāmi, the son of Vyāsadeva, used to wander the forests absorbed in brahman realization, and indifferent to all material necessities. To bring him to his āśrama, Vyāsadeva engaged a group of woodcutters, instructing them to chant the following verse while moving through the forests—

nivṛtta-tarṣair upagīyamānād bhavauṣadhāc chrotra-mano-’bhirāmāt

ka uttamaśloka-guṇānuvādāt pumān virajyeta vinā paśughnāt

Those whose thirst has been fully quenched come and sing this song. It is the medicine — the solution to birth and death — and it is always pleasing to the senses. The senses should not be seen as eternal enemies to be rejected, but rather as faculties that can be properly engaged. This song is sweet to all the senses. Both the ear and the mind are delighted by its higher joy. Who but a self-destructive person would distance themselves from such a vision of life, such an ideal? Only one who is blind to their true interest would do so. Anyone awake to their real welfare can never turn away from the praise and glorification of the Supreme Lord — the highest conception of life, one that surpasses even mokśa.

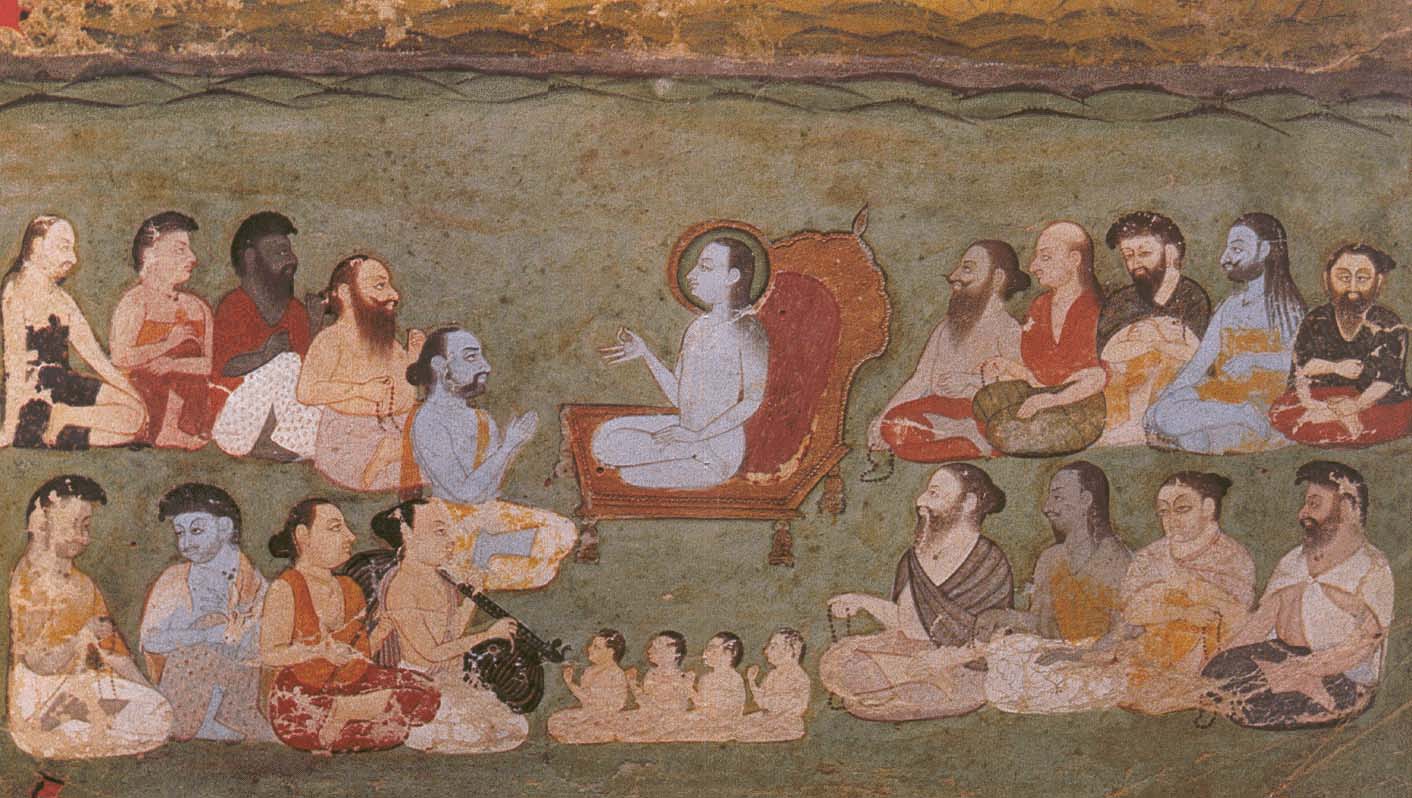

Eventually, Śukadeva heard the singing of the verse and was immediately drawn to it. He was brought to Badarikāśrama, to the place of Vyāsa, and there he inquired from his father about the meaning of the śloka. Śrī Vyāsadeva explained it to him in accordance with the insight he had received from Devarṣi Nārada. Later, the Bhāgavata was discussed at Śukatīrtha (near Bijnor, UP) by Śukadeva Goswāmi at the sabhā of Parīkṣit Mahārāja, and by Sūta Goswāmi at Naimiśāraṇya (northwest of Lucknow, UP).

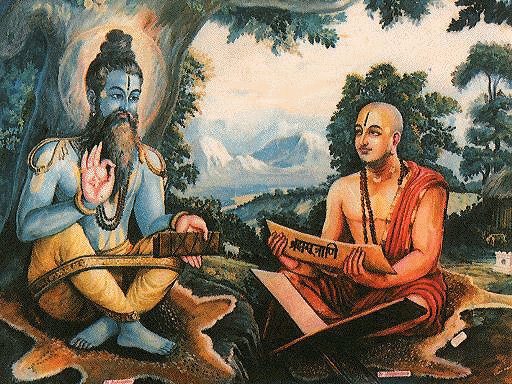

Madhvācārya, the 13th-century proponent of Dvaita Vedānta, is particularly known to have undertaken pilgrimages to Badarikāśrama to seek Vyāsa’s blessings and to deepen his understanding of the Brahma Sūtras. There, Madhvācārya observed 48 days of fasting, silence, and meditation at the temple of Badrinath. At the end of this period, Veda Vyāsa appeared and invited Madhvācārya to His āśrama. Madhvācārya then journeyed to Vyāsa’s āśrama, where he offered his newly composed Bhagavad Gītā Bhāśya, which Śrī Vedavyāsa listened to and approved.

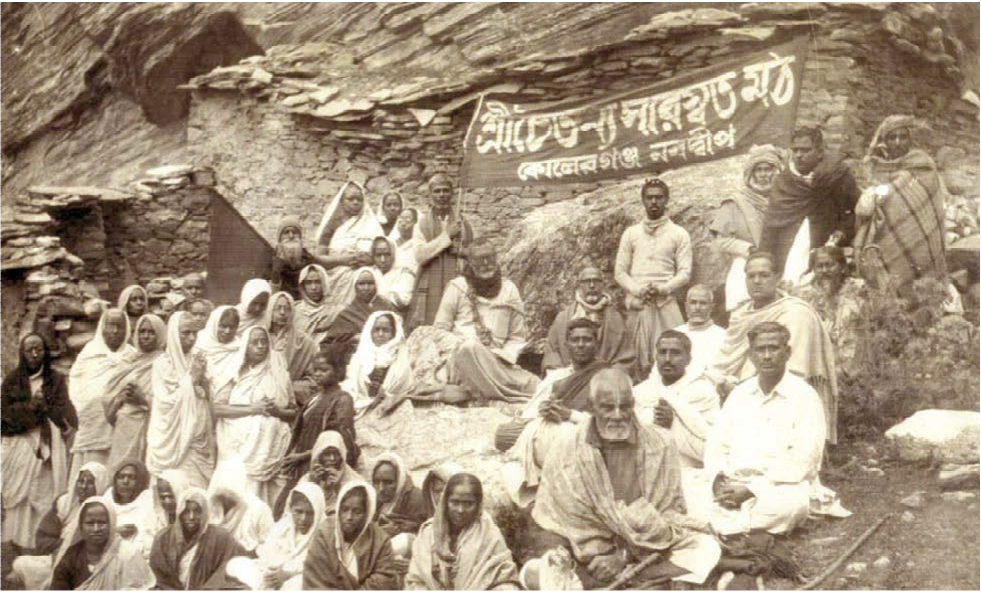

It was not until the advent of Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu that harināma-saṅkīrtana, the final recommendation of Śrīmad Bhāgavatam, was given full emphasis, and the pañcama puruśārtha of divine love of Śrī Kṛṣṇa (Kṛṣṇa-prema) was established as the ultimate goal of life. Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura had a vision that the Saraswatī river that flows near Badarikāśrama flows as the Jalangi River in Navadvīpa (Bengal), where the bhāgavata-dharma originally introduced at Badarikāśrama, reaches its highest expression in the teachings of Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu.

Śrīla Śridhar Mahāraja is also known to have visited Vedavyāsa’s cave at Badarikāśrama. He recounts the following conversation—

I once met a scholarly sannyasi in Badarikāśrama who posed as an atheist in the course of our discussion. He argued, "What is the evidence that God or the soul exists?” Then I quoted a verse from Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam (11.22.34):

ātmāparijñāna-mayo vivādo hy astīti nāstīti bhidārtha-niṣṭhaḥ

vyartho ’pi naivoparameta puṁsāṁ mattaḥ parāvṛtta-dhiyāṁ sva-lokāt

I explained to him that although atma, spirit, is self-effulgent, there is a constant quarrel between two opposing parties. One party says, "God exists!" The other says, "God does not exist!" Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam says that the atma is self-effulgent, but still we find that one class of men say, "He exists, we see Him, He can be seen," and another says, "He has never existed." This quarrel has no end because one of the parties hasn't got the eye to see what is self-evident. This quarrel is a useless waste of time, but still it will never stop; it will continue forever. Why? Because there are those who have the eyes to see God and those who have no eyes to see Him or their own self. One of these classes of men have deviated from God consciousness. There is a barrier between them and God consciousness, between them and self-consciousness. So the disagreement will only continue on account of their ignorance.

Just as the great snow-fed perennial rivers, Ganga and Yamuna, originate in the Himalayas and flow down into the plains, nourishing an entire civilization, the Vedic śāstras—the very soul of Hindu culture—also have their origin around Badarikāśrama in the Himalayas, from where they were spread and established all across India through the efforts of great sages and their saṁpradāyas. Devotees drawn towards the study of the Vedic śāstras, particularly Śrīmad Bhāgavatam, feel some affinity towards Śrī Vyāsadeva’s cave at Māṇa village. They come here hoping to deepen their spiritual understanding and draw further inspiration for studying the śāstras.

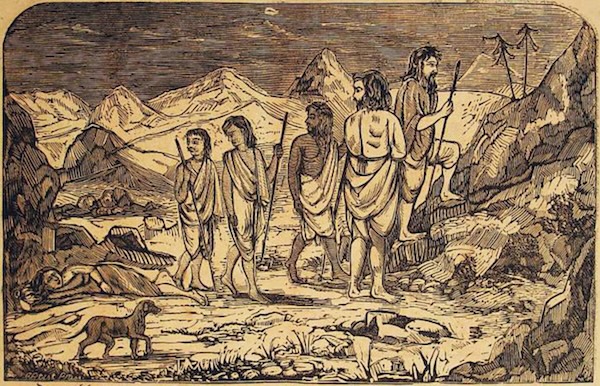

Before motor vehicles and proper roads were introduced in the Himalayas, the pilgrimage to Badrinath was an intensely austere experience. Situated at an altitude of around 10,000 feet (3,300 meters), the journey had to be made on foot or by pony, often taking days of difficult travel through rugged terrain. Facilities along the route or at the destination were minimal, yet those who undertook this once-in-a-lifetime journey expected little on this aspect. It was a path reserved for the truly resolute. The following description offers a vivid depiction of the experience of walking such a pilgrimage. The passage is from Prabodh Kumar Sanyal’s Bengali work Mahāprasthāner Pathe (মহাপ্রস্থানের পথে) — a travelogue capturing the emotional and physical intensity of a journey to the shrines in the Himalayas.

Before motor vehicles and proper roads were introduced in the Himalayas, the pilgrimage to Badrinath was an intensely austere experience. Situated at an altitude of around 10,000 feet (3,300 meters), the journey had to be made on foot or by pony, often taking days of difficult travel through rugged terrain. Facilities along the route or at the destination were minimal, yet those who undertook this once-in-a-lifetime journey expected little on this aspect. It was a path reserved for the truly resolute. The following description offers a vivid depiction of the experience of walking such a pilgrimage. The passage is from Prabodh Kumar Sanyal’s Bengali work Mahāprasthāner Pathe (মহাপ্রস্থানের পথে) — a travelogue capturing the emotional and physical intensity of a journey to the shrines in the Himalayas.

Walking continuously, we grew tired. Pain began in the feet. The heart became heavy with sadness. The whole body was covered in the dust of the road. Still, stopping was not an option. At some halts, we bought flour and lentils, cooked and ate. At others, we collapsed without food or water, lying like half-dead souls with our eyes shut. And so, day after day, night after night, we went on, dragging along the burden of our weary bodies.

It is mentioned that during their mahāprasthāna—the final journey—the Pāṇḍavas first travelled eastward from Hastināpura, then south to the ocean, followed by a westward visit to Dvārakā. Finally, they turned northward, passing through Ṛṣikeśa and reaching Badarikāśrama, from where they began the last leg of their journey—svargārohaṇa, the ascent to the heavenly realms. Before the rise of scientific and technological pursuits in India, the idea of mahāprasthāna was deeply etched in the spiritual consciousness of Hindu society. The impermanence of the body and the world, the cycle of birth and death, and the goal of mokṣa were widely accepted truths. Sensing the approach of death, devout Hindus would sometimes undertake arduous pilgrimage to the sacred Himalayas, never intending to return. They would relinquish all possessions to family and friends, and set off free from worldly attachments.

Today, the Uttarakhand chār-dhām circuit, of which Badrinath is one of the shrines, feeds substantially into the economy of the Indian state. Pilgrimages through the Himalayas, once undertaken by small groups of sincere and determined seekers, are now extensively promoted by the Government and travel businesses, and overrun by mostly a spiritual holiday crowd. Commercially laced with all grades of hotels, and related travel facilities, pilgrims have the luxury to prebook all comforts they desire for their visit, and still complain about it in the end.

A string of small shops and stalls now lines the path leading up to Vyāsadeva’s cave at Māṇa, a place that once inspired deliberations on Vedic philosophy. Among them, a tea shop located directly beside the cave has gained particular attention, having been branded as "India’s first tea shop" (भारत की प्रथम चाय की दुकान), a claim based on Māṇa being the last Indian village before the China border. Ironically, the tea stall has become a popular stop for pilgrims, many of whom seem to lack a sense of context about what is appropriate next to a sacred site. India’s obsession with chāi (tea) has disturbingly encroached upon the dignity of a space that originally encourages austerity and renunciation for a higher understanding. This instance may just be the tip of the iceberg, revealing a deeper crisis within Hindu society, one of apathy and disregard toward the roots of its own culture. Legend has it that Śrī Vyāsadeva silenced the roaring Saraswatī river by forcing her to go underground so that he may focus on his writing work. Perhaps our tea-sipping pilgrims next door could take a hint, and seek their refreshment elsewhere.

Footnotes

[1] The ciranjeevis are seven immortal personalities in Hindu tradition who are believed to live until the end of the current age of kali-yuga. They are Aśvatthāmā, Bali Mahārāja, Hanumāna, Vibhīṣaṇa, Kṛpācārya, Parāśurāma, and Vedavyāsa.