We recently heard from a senior sannyāsī guru living in Vrindavan, India, who spoke openly about the qualifications needed to accept sannyāsa and serve as ācārya. He expressed concern that taking on these roles without enough age, maturity, and training under a senior leader in an institution can cause serious problems — not only for the person accepting the role but also for those they guide and even for the guru who conferred the sannyāsa. He mentioned that such a lack could cause a guru to become a dictator instead of a humble servant. He hinted that youth and ambition often go together. In his view, younger sannyāsīs or gurus are at risk of taking on such responsibilities too early. He also stressed that the purpose of the guru when giving sannyāsa should be clearly understood — whether it’s to prepare the disciple for lifelong service in an established āśrama or to eventually become an ācārya. He implied that following his own way of thinking — one emphasizing institutional training, senior association, clarity of guru intention, and readiness based on age — was the safer, less risky course and would help guard against future regret and sorrow for someone assuming the roles of sannyāsī and guru. He implied that his approach was the safer course—one that would prevent later regret or sorrow.

Maharaja began his address by first asserting that “the age of a devotee may not be the main point,” implying that age may not be a determining factor for spiritual leadership. This statement is indeed supported by śāstra. The Bhagavad-gītā (4.34) clearly states that the qualification of a guru is realization—tattva-darśinaḥ, one who has seen the truth—without any reference to age. Similarly, Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu affirms in Caitanya-caritāmṛta (Madhya 8.128), “kibā vipra, kibā nyāsī, śūdra kene naya / yei kṛṣṇa-tattva-vettā, sei ‘guru’ haya”—“Regardless of one’s varṇa or āśrama, if one knows the science of Kṛṣṇa, he is qualified to be guru.” This principle is further echoed in Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam (1.2.12) “The seriously inquisitive student or sage, well equipped with knowledge and detachment, realizes that Absolute Truth by rendering devotional service in terms of what he has heard from the Vedānta-śruti.” Scriptural history provides further evidence: Prahlāda Mahārāja spoke deep truths as a mere child, Jīva Gosvāmī became a profound ācārya in his youth, and Nārada Muni attained perfection as a boy. These examples affirm that true spiritual authority is rooted in realization, not chronology.

However, while śāstra does not prescribe age as a formal qualification—and Mahārāja first acknowledges this—he then recounts how Śrīla Śrīdhara Mahārāja hesitated to grant him sannyāsa due to his youth. Yet we know from history that Śrīla Śrīdhara Mahārāja gave encouragement and even adjusted the names of some younger sannyāsīs from his godbrother’s mission, Śrīla Bhaktivedānta Swami Prabhupda’s mission. Our Guru Mahārāja was one of them. Some of those sannyāsī-gurus were already serving in the role of ācārya when they received his blessings. And sadly, even after receiving Śrīla Śrīdhara Mahārāja’s blessings and instructions, some of those young sannyāsīs who were already playing the roles of acharyas later became offensive to him—offenses that have left lingering effects and continue to spoil the integrity of Śrīla Bhaktivedānta Swami Mahārāja’s mission. Others who were sincere like our guru Maharaja were very benefitted by Srila Sridhara Maharaja and later were chosen by Mahaprabhu to act as acharyas. This reveals a sobering truth: that even the association and guidance of senior sādhus, though beneficial and recommended, is not a guarantee that one will actually benefit. Inner transformation might not come after years of training or it may come in days.

It was seen that in the time of Srila Bhaktivedanta Swami, he discouraged his disciples from seeking śikṣā from many of his godbrothers who were all elderly Vaishnavas. At that particular time, he knew it would not benefit them. That instruction was later rescinded when Srila Bhaktivedanta Swami made amends with his godbrothers before his passing. and even referred to Srila Bhakti Raksadka Sridhara Deva Goswami Maharaja as his śikṣā guru. Although Srila Sridhara Mahārāja did, on occasion, give sannyāsa to the young. he upheld a more cautious and conservative approach—preaching primarily within India—Śrīla Bhaktivedānta Swami Prabhupāda was fighting a spiritual war on a global scale. In a war with no generals, anyone who steps up may be made a general.

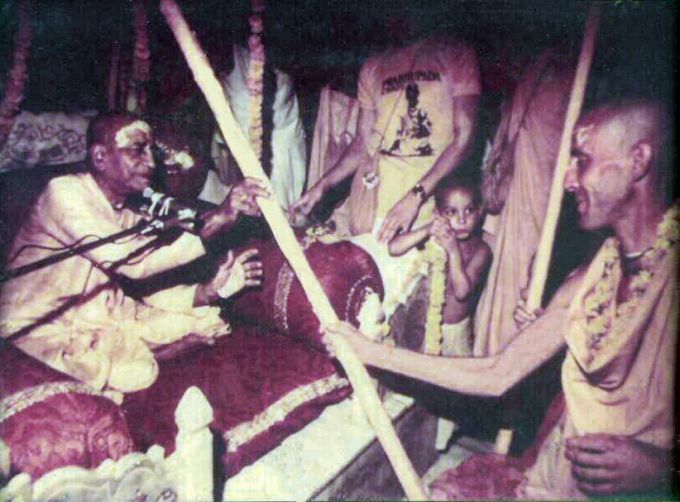

Our Guru Mahārāja, Jagad Guru Swami Bhakti Gaurava. Narasiṅgha Mahārāja, stepped up, and—due to his youthful vigor—was sent to Africa, then still referred to as “The Dark Continent,” and for good reason. Such a mission was not suited for an old man. Three years after this bold and risk-filled adventure, Śrīla Prabhupāda awarded him sannyāsa. While some have questioned Śrīla Prabhupāda’s dynamic decisions, such criticism fails to grasp the divine empowerment and necessity behind his actions. What he did was never whimsical—it was ordained by Kṛṣṇa and was a decisive, innovative step demanded by the circumstances. And although we cannot ignore the problems that later arose from the misbehavior of many sannyāsīs who appointed themselves as initiating gurus or ācāryas—and from others who fell down—we must also recognize the undeniable positive outcome: Kṛṣṇa consciousness was spread across the globe.

That being said, in the mission of our Guru Mahārāja, the Sri Narasingha Caitanya Math, it is well known—and cannot be disputed—that he actively encouraged tridaṇḍi-sannyāsa for young men following in the footsteps of Srila Prabhupada. In fact, most of his sannyāsa disciples were young or relatively young at the time they received the order. Guru Maharaja put much emphasis on youthful preaching and even said that in the mission of his guru, Srila Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, the real hope was in its youth. He said,

“…if there's any hope for ISKCON it's in the newcomers that didn’t swallow the Kool-Aid that's who will change things long after I'm gone it won't be any of these old people—none of them, none of them. They can't do anything they've all got to just go.”

Our Guru Mahārāja was so inclined toward awarding sannyāsa to the young that, in the early 2000s at Govindajī Gardens in South India—his central āśrama—he even considered reviving the rare tradition of bāla-sannyāsa (renunciation accepted in childhood) for a boy brahmacārī disciple. Though the plan was eventually set aside, the very consideration reveals his deep conviction that youthful energy and dedication are ideal for embracing the renounced order and boldly preaching the glories of the Holy Name. While bāla-sannyāsa has historical precedent—most notably with Śaṅkarācārya, and occasionally within the Advaita and Śrī Vaiṣṇava traditions—it has always remained a rare exception.

This emphasis on youthful renunciation finds clear precedent in the life and mission of Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Ṭhākura, who instituted the tridaṇḍi-sannyāsa order not as a retirement plan, but as a dynamic vehicle for preaching to facilitate widespread distribution of our Gaurangas Saṅkīrtan. Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Ṭhākura instituted the tridaṇḍi-sannyāsa order and conferred sannyāsa upon many young, energetic brahmacārīs. This dynamic was continued by some of the stalwart disciples of Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Ṭhākura after his disappearance, as they took up the charge of ācārya. It is also worth noting that Śrīla Śrīdhara Mahārāja was especially generous toward those who had accepted sannyāsa but later fell from that position. He emphasized that even those who attempted the renounced order—though they may not have succeeded—should be honored for their endeavor.

In his discourse, the Mahārāja raises the question of whether one has received sufficient training, and it is well known that our Guru Mahārāja was indeed eager to personally guide his newly initiated sannyāsīs so that they might imbibe the proper mood and conduct of the renounced order. However, in the case of Śrīla Bhaktivedānta Swami Mahārāja, when he initially approached one godbrother for sannyāsa, he was told to first reside in that Maṭha so his qualification could be assessed. Śrīla Bhaktivedānta Swami did not accept that stipulation and instead received sannyāsa from Śrīla Bhakti Prajñāna Keśava Mahārāja, who did not require prior residence or training under him. This clearly shows that while close association and training under one’s sannyāsa-guru may be ideal, it is not an absolute law. The essential qualification lies in sincerity, not institutional formality. Case in point: history shows that one of Śrīla Prabhupāda’s own disciples, who had little personal training under him, one Siddhaswarupananda Goswami, later became a jagad-guru and leading ācārya on the global stage, amassing the greatest number of followers outside Śrīla Bhaktivedānta Swami’s mission. This again underscores that spiritual empowerment does not rest solely on external association, but on inner surrender, and faithful adherence to the divine orders of our Guardian Acharyas.

Concerning the position of ācārya, we can observe from recent history that some of the most successful and dynamic spiritual leaders attained that position at a young age. Some of the prominent acharyas walking amongst us today, especially in the west were called at a relatively young age.

Maharaja raises the question of intent—whether one has been explicitly instructed by one’s guru to accept the role of guru or ācārya. But throughout the history of our paramparā, many empowered ācāryas have emerged without receiving a direct, verbatim command to initiate or formally take up leadership in the capacity of acharya. Rather, their qualification was recognized through their realization, character, and seva. It is the implicit and universal intent of every genuine ācārya that his disciples advance to the platform of prema-bhakti and become capable of guiding others. As Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakur stated, “I don’t make disciples, I make gurus.” When Śukadeva Gosvāmī appeared on the scene of Parīkṣit Mahārāja’s impending death, no one questioned whether he had received formal authorization to speak the Bhāgavatam—his purity and realization alone gave him authority. Similarly, Prahlāda Mahārāja, though a mere child and without any dīkṣā-guru present in his early life, became a mahājana and spiritual guide from his childhood. In Caitanya-caritāmṛta, Lord Caitanya proclaims, “yāre dekha, tāre kaha 'kṛṣṇa'-upadeśa”—instructing every devotee, regardless of formal title, to become a guru by sharing Kṛṣṇa consciousness. And who could forget Gopala, the boy associate of Mahāprabhu, who was nicknamed ‘Guru Gopala’ by the Lord Himself due to his unwavering dedication to the Holy Name. By his example, he instructed even senior devotees in the supreme efficacy of chanting the Holy Name while a young boy.

While explicit instruction may help clarify a guru’s desire, the absence of such wording does not negate divine empowerment. Throughout our paramparā, many ācāryas were not formally appointed, elected, or named as successors. Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Ṭhākura did not designate a single successor, yet his disciples continued his mission based on their realization and sevā. Similarly, Śrīla A.C. Bhaktivedānta Swami Prabhupāda’s most dynamic and empowered followers rose to prominence not through official appointment, nor through any type of ecclesiastical framework or voting system, but through their unwavering dedication and effectiveness in spreading Kṛṣṇa consciousness.

In truth, every successful ācārya is appointed—but that appointment rests at the feet of our Dear Lord Gaurāṅga. To material eyes, this may sometimes manifest as an explicit, verbatim instruction from the guru, and at other times it may not. Divine sanction cannot be reduced to a paper trail. Moreover, it should be understood that even a formal appointment or any ecclesiastical arrangement does not guarantee success. Just as receiving first initiation offers an opportunity, not an assurance, of perfection. We personally witnessed this reality when our Guru Mahārāja made an explicit appointment. The appointee, despite having received formal endorsement, the long-time association of senior Vaishnavas, training under our Guru Maharaja for years and years, and the blessings of our Guru’s saṅgha later voluntarily stepped down because he could not maintain the order due to behavior unbefitting an acharya. This serves to illustrate that true appointment does not rest upon a document or formal proclamation, but upon the divine qualities of realization, humility, and empowerment that manifest in a disciple who is genuinely receptive to such divine grace.

The examples of living acharyas today, appointed at a young age highlight a crucial point: age and background are often misused as measures of spiritual credibility. There exists a line of thinking— shaped by prejudice and spiritual ignorance—that places undue emphasis on external or relative factors such as age, nationality, or cultural background. For instance, foreign (non-Indian) leaders are frequently viewed as less qualified or more prone to deviation or spiritual downfall, while older or ethnically Indian gurus are automatically assumed to be more trustworthy or authentic. This way of thinking lacks objectivity, fairness, and spiritual insight. True qualification lies in realization, character, and fidelity to the siddhānta—not in the superficial attributes that the world may elevate.

One occasion when our Guru Mahārāja was recommending a friend to consider taking shelter of Śrīla Bhakti Promode Puri Gosvāmī Maharaja. The man responded by saying, “He is old, he is Indian, and he is from the Gauḍīya Maṭha—what a good choice!” Guru Mahārāja was visibly dismayed by this response. Indicating that such external considerations have nothing to do with true spiritual qualification. Śrīla Puri Mahārāja’s real qualification lay in his profound advancement in Kṛṣṇa consciousness, his spotless character, and his deep love for the Supreme Lord and surrender to his guru Sarasvati Thakur. To judge the worth of a spiritual master by age, ethnicity, or institutional affiliation or any other external thing is to miss the essence of guru-tattva. As Śrī Caitanya Mahāprabhu declared, “kibā vipra, kibā nyāsī, śūdra kene naya, yei kṛṣṇa-tattva-vettā, sei ‘guru’ haya”—“Whether one is a brāhmaṇa, a sannyāsī, or a śūdra—regardless of what he is [birth or background]—if he knows the science of Kṛṣṇa, he is to be accepted as a guru” (Cc. Madhya 8.128).. Similarly, the Padma Purāṇa states—“A scholarly brāhmaṇa expert in Vedic knowledge is unfit to be a spiritual master if he is not a Vaiṣṇava, but a true Vaiṣṇava—even if born in a family of dog-eaters—can become a genuine guru.”

In the eyes of our Guru Mahārāja, Śrīla Puri Mahārāja embodied those rare and sacred qualifications found in a pure sādhu. Age, Math affiliation and being born in India were not the primary qualifications.

The Mahārāja asserts that institutional training is very important and cites certain Maṭhas. While the concern for proper training and association is certainly valid, the assertion that these alone reduce the ‘risk’ of one prematurely assuming the role of a sannyāsī or ācārya overlooks the historical record within the very institutions being referenced. Mahārāja appeals to the authority of established missions like ISKCON and the Gauḍīya Maṭha, yet the reality is that many of those who received sannyāsa in such institutions—with all the formal training, association, and senior guidance—eventually fell down, sometimes disastrously. This proves that institutional training, while helpful, is no guarantee of purity, humility, or spiritual realization.”

To argue that the risk is less when one has had the type of training he referred to is speculative and selectively optimistic. The past clearly shows that formal systems of training and designation often did little to prevent ambition, pride, or moral failure—even among those handpicked by prominent ācāryas. Thus, using institutional training as a metric of qualification becomes circular: it presumes that the institution is capable of producing qualified leaders when its own history frequently disproves that.

Mahārāja asserts that accepting sannyāsa at an early age, or prematurely assuming the role of ācārya, is dangerous and may stem from ambition that could lead to dictatorship. Yet the notion that age itself inherently guards against such ambition is both naïve and overly simplistic. In truth, ambition can quietly persist into old age or resurface unexpectedly after years of apparent renunciation. Since the departure of Śrīla A.C. Bhaktivedānta Swami Prabhupāda, the Vaiṣṇava world has witnessed numerous cases of older, seasoned Vaiṣṇavas—despite having all the training, association, and years of experience—still succumbing to ambition and the subtle intoxication of influence and control.

It is a fact that the Acharya is, by position, an autocrat—but his authority is governed by pure love, not force or control. When that love is absent, there is always the risk that such authority can devolve into dictatorship. Personally, we have never witnessed such a distortion firsthand, but historically, it is possible that it has occurred. Still, the real culprit is not youth—it is false ego and unaddressed anarthas, which can afflict a person at any stage of life. To suppress or bridle youthful energy out of fear of ambition is to cripple the very momentum of the movement that has to a large degree been carried by young people. Especially in the earlier days of Mahaprabhus saṅkīrtan in the west. The history of our sampradāya is filled with dynamic, youthful devotees whose spiritual depth and surrender qualified them to lead and inspire.

What truly qualifies someone is not institutional backing, seniority, or the passage of time, but internal realization, genuine humility, and a heartfelt desire to serve the mission of the previous ācārya in the line they are representing.

The fear that someone may become a “dictator” rather than a “humble servant” is not resolved by simply delaying sannyāsa or relying on institutional training. The real safeguard is found in cultivating deep relationships with genuinely realized sādhus—whether through close physical proximity or from afar—and earnestly aligning oneself with their mood and instruction. It is not vapu—the nearness of the physical body—but vāṇī, following the instruction of guru, that protects one from deviation. Many stood near the body of their guru, yet drifted. Others, separated by time and distance, remained fixed through faithful adherence to his words. Physical closeness, though helpful in some cases, is not the real criterion for spiritual advancement. Some stood near yet were spiritually far, while others stood far yet remained spiritually close to their guru. Srila Prabhupada had little physical association with his guru Sarasvati Thakur.

Even a moment’s association with a genuine sādhu is powerful enough to propel one forward on the path of perfection. As confirmed in the Caitanya-caritāmṛta (Madhya-līlā 22.54): “Sādhu-saṅga, sādhu-saṅga—sarva-śāstre kaya / lava-mātra sādhu-saṅge sarva-siddhi haya”—“The verdict of all revealed scriptures is that by even a moment’s association with a pure devotee, one can attain all perfection.” Such is the transforming potency of true saintly association: even the briefest contact with one who embodies devotion can awaken faith, inspire surrender, and redirect the course of a soul’s destiny. Yet the same śāstra and ācāryas also caution that overfamiliarity—too much close association with a saint without reverence—may lead to offense. As Śrīla Prabhupāda warned, “too much familiarity with the pure devotee sometimes breeds contempt.” When awe and respect are replaced by casualness, one may begin to see the sādhu in material terms, thus forfeiting the very benefit of that sacred association.

Thus, we see that close personal association with a sādhu also carries inherent risk. It is not an absolute that such proximity or training will yield the intended spiritual result. In the same way, some mistakenly think that long-term residence in Vṛndāvana automatically equates to spiritual advancement. Yet wherever a pure devotee is present becomes as good as Vṛndāvana, for the essence of Vṛndāvana is the presence of pure devotion. Residence in the dhāma is not a prerequisite for spiritual life, and for those not properly qualified, prolonged stay in Vṛndāvana can be spiritually damaging—just as overfamiliarity with a pure devotee can diminish, rather than enhance, one’s bhakti.

Our Guru Mahārāja was adamant that Vṛndāvana is the place for paramahaṁsas, not for ordinary people. He strongly decried those born outside the Dhāma who engaged in household sex life within the holy land. He also condemned the notion of certain mothers going to the Dhāma merely to give birth so their children could be called Vrajavāsīs. On these issues he was unwavering and would not move an inch. Grounded in the pure siddhānta of our Guardians, he would never rubber-stamp such behavior. Without proper guidance under the order of Śrī Guru, and without intense service, he heavily frowned upon residence in the Dham.

This uncompromising stance on the sanctity of the Dhāma was part of a larger principle he upheld: that spiritual life must be taken seriously, never reduced to a matter of external appearance, birthright, or prolonged formality. Just as he would not tolerate the Dhāma being treated in an ordinary, material way, he likewise rejected the notion that advancement in bhakti is dependent merely on the passing of time or years of institutional ‘training.

Years and years of association are not always required, nor is an extended period of so-called “training” the true prerequisite for advancement. Our Guru Mahārāja used to say that one should remain on the neophyte platform for only a few days—otherwise, there may be something wrong with one’s teacher. Of course, he was exaggerating to make a point, but the message is clear: if a disciple remains stagnant after years of sincere effort, the deficiency may not be in the student, but in the guidance they are receiving. A genuine guru should be able to awaken and nourish a sincere disciple’s spiritual progress in a tangible way after a relatively short period of time. No one should be an eternal neophyte.

Bhakti cannot be mass-produced by bureaucratic systems; it is transmitted by heart-to-heart connection with realized souls.

It is well known that in the mission of our Gurudeva, he explicitly stated that only sannyāsīs should assume the role of ācārya. While he acknowledged—consistent with the teachings of Mahāprabhu and the ācāryas—that anyone who truly understands the science of Kṛṣṇa consciousness can become guru. Within his own mission he clearly directed that this responsibility be carried forward by his sannyāsī disciples. This instruction was documented in his wills and confirmed multiple times during his life. He also emphasized that his disciples should not seek śikṣā outside his mission except in truly exceptional circumstances—not due to a lack of qualified ācāryas elsewhere, but because he had already given the distilled teachings of Śrīla Prabhupāda, Śrīla Bhakti Raksaka Śrīdhara Deva Goswami Mahārāja, and Śrīla Bhakti Promode Puri Goswami Mahārāja. His desire was that the branch he established be continued in his own mood and under the leadership of those he had personally initiated—not by others, and certainly not by any godbrother stepping into his shoes or veśa.

“No godbrother of mine outside of our mission is welcome to come and try to take over Guru Maharaja’s mission.”

—Guru Mahārāja

Tragically, much confusion and division arose when this clear instruction of Guru Mahārāja was disregarded. All of his directions are available in his written wills. Although our Guru Mahārāja’s will cannot be confined to mere paper and ink, its spirit was clearly reflected in the legal documents he left behind.

Guru Mahārāja clearly stated:

“If for some reason a sannyāsī cannot fit into the environment amongst the devotees of the āśrama, he is free to start his own mission.”

But such independence was never intended as a license for divisiveness or spiritual elitism. Any party branching out under that instruction would never stoop to ridiculing Guru Mahārāja’s central branch at Govindajī Gardens—or to minimizing the ācārya there on the basis of age or any other external designation—because that central branch faithfully follows his instructions and embodies his mood.

Yet history shows that when a branch separates from its guru’s mission and seeks to present itself as the sole authentic representative of the paramparā, the mentality of amar guru jagad guru—that only one’s own guru is qualified and all others are lesser—inevitably emerges. Such a mindset has no place in the worldwide mission of Mahāprabhu. Our Guru Mahārāja despised the notion of a group propping up its own standing by claiming exclusive authenticity and diminishing other bona fide gurus for the sake of building its own mission. There are no monopolies in our Bhāgavat Paramparā.

In his talk, Mahārāja emphasized that the guru’s intent in awarding sannyāsa is very important, even questioning whether the guru himself had asked a disciple to take sannyāsa. By this, if a disciple requests sannyāsa on their own initiative, it might not align with the guru’s intention and could be considered inappropriate. For our Guru Mahārāja, however, whether a disciple directly asked him for sannyāsa or he offered it himself was not the key—what mattered was the disciple’s sincerity in serving his mission. Some like myself were personally invited by Guru Mahārāja to accept the renounced order, while others stepped forward on their own. Following his own example of approaching Śrīla Prabhupāda for sannyāsa, he saw no conflict in giving others the same opportunity. His goal was always clear: to empower qualified disciples to carry out the mission by taking responsibility—to instruct, and, when called upon, to accept the role of guru in the capacity of acharya.

Concerns for the integrity of guru-paramparā must be expressed sincerely. If we are truly concerned about the health and continuity of the disciplic succession (paramparā) and the proper guidance of spiritual seekers in the modern age, then our concerns must be voiced with honesty, transparency, and consistency—not with hidden agendas, subtle biases, or double standards. All of which can—and, as we have seen from history, sometimes do—manifest in old age. The future of Kṛṣṇa-bhakti rests not in the hands of institutional gatekeepers, but in the hearts of those who possess clear purpose, genuine realization, and the fearless integrity to follow in the footsteps of our Guardians, the great ācāryas. Young or old, those called must step up and lead.

While the sentiment “Better safe than sorry” may seem prudent on the surface, spiritual leadership cannot be approached with the same cautious conservatism used in mundane risk management. The path of bhakti is not driven by safety, but by surrender, faith, and the courage to follow the order of guru—even when it defies worldly logic. Our Guru Mahārāja did not take the “safe” route when he accepted sannyāsa at a young age, nor when he conferred it upon others who were likewise youthful. Bhakti is a realm where boldness in service, when guided by genuine surrender and śraddhā, yields the greatest spiritual outcomes. No risk no gain as Srila Sridhara Maharaja said. To reduce spiritual decisions to the framework of minimizing risk is to overlook the very nature of divine empowerment—kṛṣṇa-śakti vinā nahe tāra pravartana—without Kṛṣṇa’s potency and empowerment, one cannot truly lead others. Playing it “safe” may preserve institutional image, but it can also stifle the dynamic spirit of preaching and, in doing so, minimize the expansive, liberating power of the Holy Name. True spiritual vitality arises not from control, but from surrender to the will of the Lord and fearless trust in His divine empowerment. It’s not safety that guarantees success—it is sincerity, surrender, and faith.. Kṛṣṇa always protects His devotees when they take bold risks. Without those greatly bold risk-takers, at least those of us born outside of India would never have come into the fold of our Dear Lord of Love, the magnanimous Golden Volcano of Pure Love, Śrī Kṛṣṇa Caitanya Mahāprabhu, the Golden Avatar.

With all the humility I can muster, I place my head at the feet of our mission ācāryas—Śrīla A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupāda, Śrīla Bhakti Rakṣaka Śrīdhara Goswāmī Mahārāja, Śrīla Bhakti Promode Puri Goswāmī Mahārāja, our beloved Guru Mahārāja, Jagad Guru Swāmī Bhakti Gaurava Narasiṅgha Mahārāja—and all our guardian ācāryas, headed by Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī Ṭhākura, the greatest senāpati-general this world has ever known—all of whom fearlessly embraced danger, hardship and risks in the divine service of distributing the Holy Name, the saṅkīrtana of our most beloved Lord.

And to all those fearless ācāryas still walking among us today—taking bold risks in service to our Guru-varga—I offer my koṭi-daṇḍavat praṇāms.

We hope that this speech resonates with the younger generations who are enthusiastic to spread the message of Mahāprabhu. Carry His banner high with the strength of your youth, and let your fearless dedication awaken the world to the glories of Śrī Kṛṣṇa-saṅkīrtana.

It is our heartfelt prayer that this offering may help clear any confusion or lingering doubts that may have arisen within the sacred mission of our Gurudeva. May these words be received not as a challenge or an attack on anyone, but as a humble attempt to serve the truth and honor his legacy.

All Glories to the Holy Name of Krishna. All Glories to the Saṅkīrtan Movement of our Dear Lord Sri Krishna Caitanya Mahaprahu the Golden Avatar of Pure Love. All Glories to all the Vaishnavas. Gaura Premanandi!!!