(Translated into English from Bengali original as published by Gaudīya Vedānta Samiti in the Gaudīya Patrika, 1st year, 2nd Edition, dated 13th April 1949)

A certain Christian scholar wrote in an English periodical as follows:

Nothing has become so grave a subject of reflection for seekers of the higher life as the harmony between present scientific inquiry and the religious spirit.

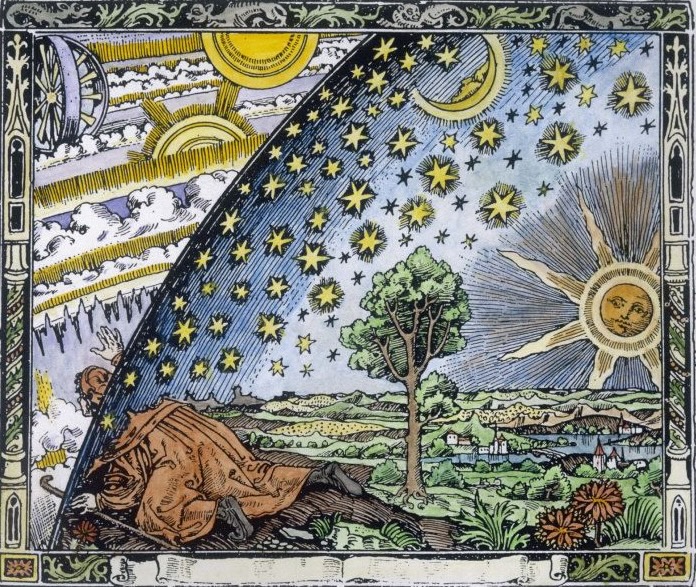

How can the intellect that discerns truth from falsehood coexist with humanity’s matter-based conclusions? And how can man’s higher, that is, supra-mundane existence be simultaneously acknowledged alongside the conclusions of physical science that establish man’s rootedness in matter? These two propositions will inevitably trouble the hearts of truth-seekers.

There is no doubt that there is a state of conflict between spiritual reason and material-scientific reason. In determining the meaning of life, this conflict is ever present; it arises from the desire to install the pursuit of knowledge in the place of the pursuit of love.

A sober examination of the claim that human life is fundamentally material, and of how far it relates to the spiritual sense, is not at all useless; rather, such inquiry is essential for all humankind. At all times and in all places, every social system up to the present has rested on a single belief: that the human being is a spiritual entity and, by his independent will, can direct his mental and physical powers. Modern science seeks to remove this belief and, in its place, to install another belief markedly different from it.

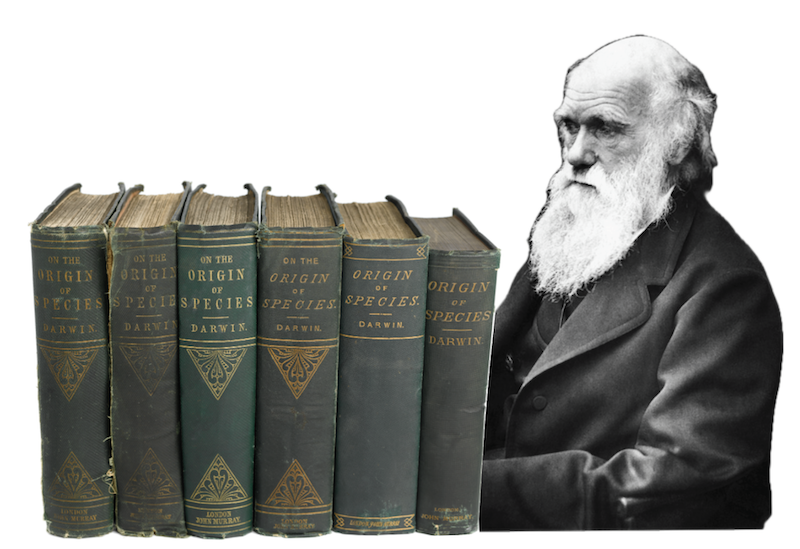

The view proposed is this: that out of the forces of mind and body, man has been produced like a mechanical contrivance of inert matter. The contrast between these two positions is stark. If one accepts the latter, not only are the ancient temples of religion and culture overthrown, but faith in them is made to vanish like a useless picture. Discrimination between true and false, judgment, mercy, hope, and forgiveness—things that now appear to us as solemn realities—would all at once become like “sky-flowers,” mere unreal phantoms. The very sense of distinction between good and evil would disappear. The man-eating demon and the benefactor Jesus Christ alike would appear as material configurations produced by prior material conditions. Like a stone slab hurled down a mountain by the force of gravity, they would be nothing but lumps of matter; there would be no need to praise or blame them, nor to feel love or hate toward them. A reading of the works of Darwin, Tyndall, Huxley, and other modern men of science will show that their opinions do not shy away from such a distorted conclusion.

When it comes to determining the inner mystery of human life, if one fully believes the aforementioned materialist view, there is no way to escape the conclusions already noted. Unless one accepts that man is merely a machine produced by matter, there appears no path to advance with the materialists. At this point, the duty of sincere inquirers is to oblige the materialists to examine their own conclusions properly and to obtain from them, in plain speech, an answer as to whether what we have said is true.

A few years ago, Llewelyn Davies wrote in an essay to this effect—

Let it be supposed that, although there is no contradiction between science and the doctrine of the soul, there is nevertheless a mutual rivalry. Now we should consider which of the two has a special claim upon our reverence. We would be satisfied if we could give equal honor to both, but we cannot. Since the materialists have conceded that science ought to be held in higher esteem, it is not out of place for us to pose the following question. Their science gives no hint of any conception of a supra-mundane life; it speaks only in terms such as evolution, transformation of energy, the course of nature and the fixed order. They themselves show regard for these doctrines. They explain all this as beautiful concepts, though they do not truly understand them. In attempting to develop these doctrines they engage in various works. As christians, we do not disparage such pronouncements by individual thinkers; but when the materialists’ science is set before us, we cannot accord it any special honor. We state plainly that our devotion to the truth of the self exceeds our regard for scientific expertise.

In our view, the real question is whether they will rely on the illumination sent from Vaikuṇṭha or not. The issue now is this: will you follow science, or will you follow knowledge of the self? Science concerns itself with what is past and with lower matters. But ātma-tattva looks to the ātmā’s future affairs and its upward course. Science, after investigating things grasped by the senses, observes how objects have gradually evolved. But by drinking the nectar of transcendental life, knowledge of the self makes one capable of composing poetry and art.

Although Llewelyn Davies’s statements are elegantly arranged, we find many points of contention in them. Throughout his piece one notices this line of thought: even though knowledge of the self, and, being shaped by religion, poetry, art, and social sentiment, may lay a greater claim on our reverence than science, nevertheless the scientific outlook on life does have some claim upon our reverence, because it is true.

However, we hold that so-called scientific conclusions, far from deserving our reverence, are thoroughly inferior. For what is called a “scientific conclusion” shows none of the marks of science. It contains propositions that have not been proved and are not even capable of proof.

Consider the real claim of the modern scientists—their central assertion is that the human being has no spiritual essence; therefore it has no role in shaping character or the progressive course of history. A devoted follower of Christ may say, “It is by love of Christ that I act thus,” but the nineteenth-century evolutionist scientists will not say so. “O Christian,” they say, “your faith is sheer delusion. Your love of Christ is nothing but a secondary pursuit to practical worldly affairs—no more than the telegraph is to the dispatch it transmits. Pleasure and pain, tears and laughter, faith, hope, lofty ambition, and love are themselves only secondary determinants of social action.”

According to reason, we may take this as the scientists’ settled conclusion. Let us then see what grounds they have for making such a claim upon humanity’s faith. The so-called scientific world today is so prostrate at the feet of Darwin’s doctrine of evolution that it takes no small courage to point out that Darwin’s “conclusion” is only a theory. From the admissions of Darwin’s devoted followers themselves it is plain that they still lack decisive proof—not only now, but such proof will always be lacking.

Seeing that from a single species many varieties of shape and color can arise by an artificial process, they have concluded that diversity of forms is born from some original form. Nature, however, never produces two things entirely alike: on a tree no two leaves are the same; no animal is in every respect identical with its mother or father. Observing such non-metaphysical facts, gardeners, stockbreeders, and many others like them have, with great effort and care, produced many diverse forms—plants and animals—out of one kind. But up to now they have not been able to combine two species and create a distinct new species.

Even evolutionists cannot deny that since the creation of man no operation of evolution is actually seen. They reply that a very long time must pass before a new species comes into being; therefore we should not hope to observe a new species so soon. But then the point becomes this: abandoning the events witnessed daily, hourly, at every moment, we are asked to accept a doctrine of unseen results—one which, by its very nature, cannot be established as a provable proposition.

Even apart from all these obstacles to accepting materialism, there is another, still more serious one. Even if one grants evolution to be true, when defining its proper scope one must admit it to be only a minor process. This doctrine is entirely silent about the source and nature of the power from which that process begins. So long as the theory occupies itself with the earth’s strata and with the forms and structures of plants and animals, it never even sets in motion an inquiry into the origin of that very operation. For this, the mechanist is satisfied. But persons of sound understanding observe that when an inquirer examines life endowed with self-evident consciousness, many kinds of realities present themselves, and the objects related to them do not lie outside the limits of self-experience.

When we reflect on joy and sorrow, pain and pleasure, words and action, we cannot know the source of their creation; only when we determine the truth of a creative power can we know it. The evolutionist, boldly yet without proof, keeps asserting that this power is produced by inert mechanisms and has no relation to consciousness. How a power that is machine-born and devoid of any connection to consciousness could generate beings endowed with spiritual independence—the evolutionist declines to conclude. On the contrary, he admits that this theory is unknowable and inconceivable. Nevertheless, even while conceding the impotence of his materialism, he most unjustly declares that those who doubt the truth of evolution are ignorant and corrupted.

There is no doubt that this essay is drawn from a Christian source. The spiritualism the author erects after rejecting materialism is only the Christian religion’s narrow doctrine of the self.

In the Christian faith there is a term (the “soul”) set forth to refute the materialists’ view. To posit it is quite necessary, for that soul is held to exist beyond all laws of material force. However, the soul as conceived in the Christian view is not the pure ātman.

The ātman intended in the Vedic scriptures—such as in the mantra “ātmā vā are draṣṭavyaḥ, mantavyaḥ” (Bṛhad-āraṇyaka Upaniṣad)—is entirely distinct from materialism and “mixed materialism.” The Christian “soul” belongs to mixed materialism. For the Christian, mind and the properties of mind are the soul; but the pure ātman is far higher and purer than mind.

Christians take the liṅga-śarīra (subtle body) to be the soul. In line with that belief they have conceived a heaven and a hell, and accordingly profess faith in a God and a Satan. Be that as it may, though Christians cannot realize pure ātma-tattva, they are to be honored above every kind of materialist, for in materialism there is simply no search for the truth of the self.

Among Christians one observes a regard for the path of the self—an esteem that looks toward freedom from scholastic and ritual fetters; this is the seed of their good fortune. This semblance of faith will, through the merit of saintly association over many births, ripen into true śraddhā in exclusive devotion.

Materialists are unfortunate: after death they attain only a state consonant with matter. “bhūtāni yānti bhūtejyāḥ” — this word of Bhagavān is the proof. By the line “yānti deva-vratā devān,” there is no doubt that Christians, devoted to a deva conception, attain the heavenly worlds of the gods. The Vaiṣṇavas who understand the import of the Veda, by the line “yānti mad-yājino ’pi mām,” in due course—by worship, offering the purified self—attain service to Bhagavān, who is the Supreme Self (Paramātman).

Materialists may rightly be called bhūtejyā, for by analyzing the laws of material entities and material forces they have formulated various rules of “progress” and “evolution,” and have accepted those rules as the chief law of the material world. After death they are cast far from ātma-tattva into matter—that is, their power of self is all but extinguished, material force predominates, and they become materialized. Their condition is pitiable. Themselves deprived, they also deprive the world; and for that offense they are, in the end, further deprived.

Such evolutionism has, from time to time, been accepted among the āryans, by many fallen persons with scholarly arrogance. There is nothing new in it. In the West, signs of human civilization and intellectual life have appeared only very recently, and so men like Tyndall, Huxley, and Darwin are counted as “learned.” They do little more than lay claim to erudition by saying old things in new language. Four thousand years ago the Bhagavad-gītā appeared; and in its description of demonic propensities it declares, “jagad āhur anīśvaram aparaspara-sambhūtam,” etc.—that naturalism, progressivism, and evolutionism all arise from such āsuric impulses.

Setting aside all these “-isms,” it is the duty of a welfare-seeking person to enter into ātma-tattva (the truth of the self). Fully acknowledging the manifoldness of the material world, one should discuss therein the līlā of the Supreme Controller and seek bhagavat-prema (love of God). It is not the task of an intelligent man to remain bound within petty doctrines.

For applied scientists, each respective science is indeed worthy of respect. Their duty is to develop science and technology, and thereby serve the knowers of truth. Ātma-tattva is exceedingly profound; those engaged in its deliberation have no leisure to be confined within ordinary pursuits of science and technology. Others should take up those concerns to provide for their bodily needs.

O brother, progressivist! O brother, evolutionist! Do your own work; in that both your good and the world’s good will be served. Do not, without proper qualification, attempt to expound the faults and merits of ātma-tattva. If you act as good men, we shall offer you our continual blessings.